Stop Playing the Numbers Game

The quantification of everything in a digital age gives us a false promise of precision in a low-resolution world

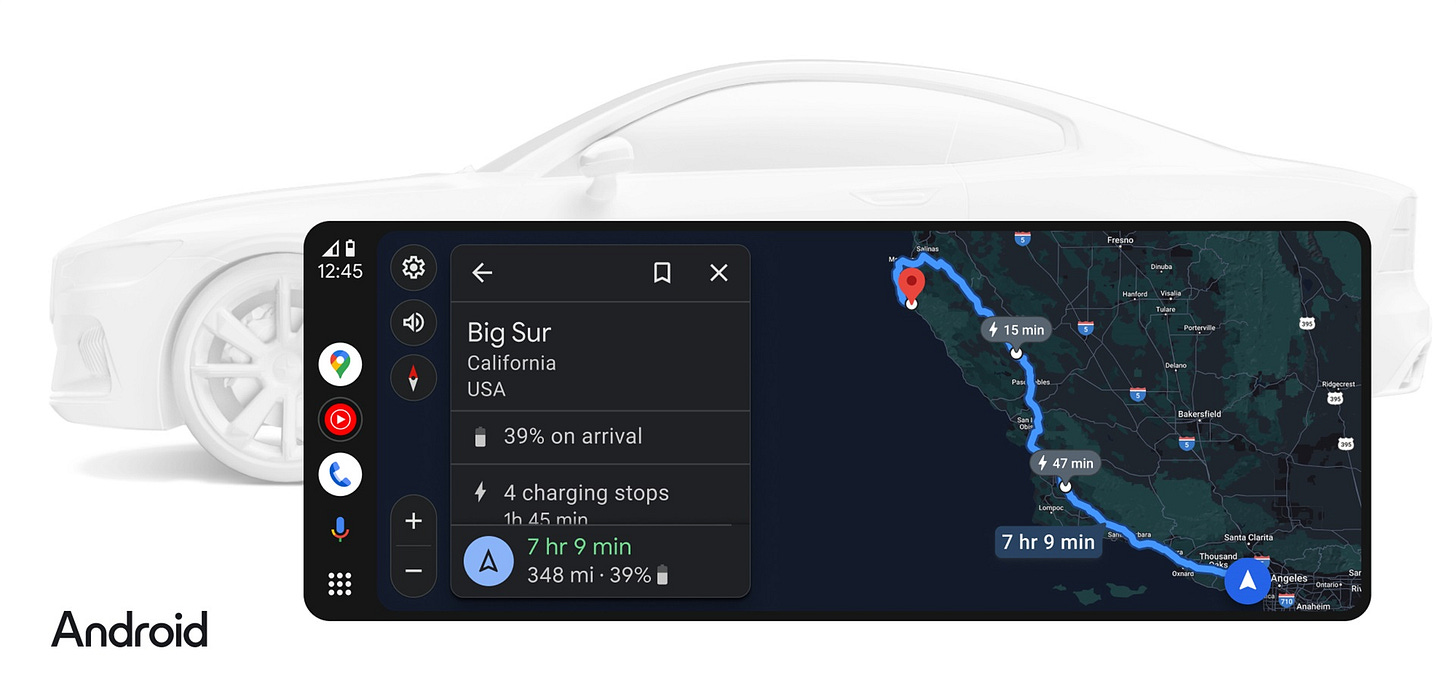

On my long recent trip to and through the Carolinas, I noticed myself frequently becoming grumpier than usual. One culprit, I realized, was the little Google Maps display with its live-updating ETA. Ordinarily, I try to avoid using navigation apps, in the old-fashioned belief that it’s better to actually know where you are and where you are going than outsource that knowledge to a computer. Increasingly, though, I have found myself still plugging my destination in to the app so that I will “know” when I’ll arrive.

Of course, I can know no such thing. Google does an abysmal job of estimating delays even from existing traffic jams, and of course it has little way of forecasting future ones. Besides, its estimates are of course derived from other drivers, who always seem to be driving faster than you are. The reality is that that little ETA number represents the earliest possible time one could conceivably expect to arrive. And yet I couldn’t help finding myself treating that number as a promise, a right, and every delay as a betrayal. I became fixated on that number and ordered all of my driving choices around it—losing the opportunity to actually enjoy the drive, with its scenery, conversation, and time for meditation.

Possibly I am uniquely pathological in this regard, but I believe this vignette represents something profound about the way that technology today rewires our expectations, our experiences, and our sense of entitlement.

In high school math and science, one of the most important things you learn is the concept of “significant digits.” If you multiply 5.3 times 16.1752, a calculator might tell you that the answer is 85.72856. But your chemistry teacher will tell you that is wrong—the correct answer is 85.9. Why? Because assuming these are two different measurements, the former is quite imprecise compared to the former (unless you know for sure that it is 5.3000)—it involves a significant rounding error compared to the latter number; maybe it’s actually 5.26 or 5.34. Thus, if you report your answer with four or five decimal points, you give the impression of having a much more precise knowledge than you actually do. Good science should convey the underlying uncertainty.

So should good ethics, politics, education, or driving navigation, for that matter. Most of the time, our grasp of most of the world is extremely low-resolution. We may have a general idea of where we’re trying to get to, how we’re going to get there, and when we’re going to get there, but any mature voyager through the world knows that all these things are uncertain and subject to revision. One of the most important lessons that we constantly try to drill into our children is to hold expectations loosely, and we are constantly exasperated by the way that they take our “yes, I think we might do that this evening” as a firm promise and inalienable right. But we do it ourselves all the time, and technology happily obliges our quest for false certainty.

Consider the weather forecast. When I was growing up, forecasts generally went five days out and used round numbers: “highs in the low 80s; lows in the upper 50s.” Today, they standardly go 10 or 14 days out and report predictions in precise numbers: High: 82; Low: 58. Many apps, competing to prove their superiority to customers, even offer wildly unscientific 15 or 30-day forecasts. Weather forecasting has gotten better over the past 30 years for sure, but still not enough to precisely pinpoint a high temperature even one day in advance. However, it is in the nature of digital communication to use precise quantities, even when circumstances don’t justify them—can you imagine if your Maps app said, “ETA: probably sometimes a bit after 3 PM”? Digital technology both caters to and reinforces our modern desire to be able to pin the world down on a bulletin board.

This trend, of course, has been in progress at least since the invention of the clock in medieval times. Much has been written about how the spread of standardized timekeeping (first clocktowers in town squares, an eventually pocket-watches and wrist-watches) gradually transformed Western culture, economics, and political life. The outbreak of World War I, it has often been remarked, was driven by the precisely-planned rail timetables in each country that determined mobilization and war plans—timetables that fostered a false sense of certainty in each of the combatant nations about how a war might proceed. The move from analog to digital timekeeping, though (from reading a clock face to reading off a series of numbers) further conditions us toward a deceptively-precise outlook on the world, thinking like the computers that we have come to rely on.

The tendency of such quantification, I have remarked above, is linked to our sense of entitlement—both as cause and effect. When I can form my expectations in terms of a precise number, I tend to latch on to that number and treat any deviation from it as a betrayal. The premodern traveler, at the mercy of bad roads or unruly waves, knew better than to hazard anything but the roughest guess as to his arrival time; today, we rant angrily at airport agents if the meticulously-tabulated numbers on the Departures board turn out to be off by a half hour. But of course, the turn to quantification is itself already in part the product of a culture of “rights.” When our early-modern ancestors began to describe moral and political life in terms of specified and enumerated rights, rather than more open-ended virtues and duties, they encouraged us to view our social lives through the eyes of accountants: what precisely is owed to me? Naturally, such an outlook on the world is profoundly unsatisfying; as we admonish our children every day, it sets you up for disappointment, and blinds you to the thousand and one unmerited, unexpected gifts that God has stored up for you. Rather than soaking in the scenery on a long drive, we fume about the slowdown that Maps warns is materializing ahead of us: “how dare these people take ten minutes of my time?!”

There is one more way, though, that this culture of quantification breeds dissatisfaction: through comparison. I’ve mentioned in a previous Substack how social media encourages us to translate qualitative experiences of social affirmation into quantitative ones: I measure my meaning not through the finely-shaded and incommensurable pleasures of a child’s embrace or a colleague’s pat on the back or a boss’s “well done,” but through a running tabulation of “likes” and “retweets,” the vast majority of them by people whom I don’t know from Adam and might not like or respect if I did know them! Not only does this quantification of my value replace a real, oxytocin-based sense of fulfillment with a hollow dopamine substitute, but it is not likely to outlast a glance at my friend’s feeds. For what use to me is 84 likes if my peer got 220? We are a constantly-comparing species, for good and for ill—but our tendency toward pathological sidelong glances can at least be thwarted by incommensurability: that is, if the goods I’m enjoying are qualitatively different from those my friend is enjoying, it can be hard to really compare them and I might give up trying. If, however, both can be reduced to a single number, offering a false sense of precision, my comparison mode is likely to go into hyperdrive. Stripped of context and quality, and reduced to mere numbers, the goods I’m enjoying (my kids’ grades, my salary, my house’s Zillow value, my church’s membership numbers, and of course my social media following) cease to be experienced as “good” unless they can be experienced as “higher than someone else’s.”

So my advice—to myself first, and to you if you need it—is this: stop playing the numbers game. Stop looking obsessively at numbers that can’t actually tell you anything meaningful. Start actively cultivating the habit of speaking in more vague or imprecise terms when describing a situation or hazarding a prediction about any situation where you have only a low-resolution view (which is, let’s be honest, most of them). Even if your computer or smartphone gives you an exact number, don’t repeat it, but translate it into a range. You’ll find that instead of constantly missing your targets and expectations, you generally start hitting them. And wherever you’re going, you might start enjoying the journey a bit more.

Newly Published

“Of Course TikTok Knew” (WORLD Opinions): My latest piece for WORLD, responds to the recent shocking-but-really-not-shocking revelations that TikTok executives knew well from their own internal research that their product was addictive and exploitative especially to their “golden audience,” young teens, knew that their various advertised safeguards had little effect, and were just fine with that. The revelations emerged in the course of a 14-state coordinated lawsuit against the tech giant that could represent a moment of reckoning for the industry.

“Review of Natural Law: A Short Companion” (Ad Fontes): This was actually published last week but I forgot to spotlight it. In the latest issue of Ad Fontes, I have a review of David VanDrunen’s newest book, Natural Law: A Short Companion. I’ve crossed swords with VanDrunen a number of times over the years, and I was involved in publishing a similarly-purposed book a few years ago, Natural Law: A Brief Introduction and Biblical Defense, so you might think I wouldn’t be a fan of this. But I am. Although VanDrunen’s book might not do everything you’d want a Protestant layman’s intro to natural law to do—there’s almost no consideration of its philosophical aspects for instance—it does what it sets out to do very well indeed. That is showing how Scripture itself teaches, presupposes, and makes use of natural law, likely to be a very persuasive approach for evangelicals.

“After the Flood” (Compact): I highlighted this last week, but it’s an important enough piece I thought I’d put it here again. Our trip to hurricane-ravaged Western North Carolina a couple weeks ago made a deep impression on us, simultaneously offering a picture of the extraordinary resilience of the American people and the extraordinary fragility of the American state. In this long-form essay for Compact, I not only narrate what we saw and share the stories of some of the remarkable locals we met, but seek to draw out larger lessons about the state of the union and how we can revive public trust in preparation for future natural disasters.

Coming down the Pipe

Faithfulness as Christian Citizens Video recordings (Ridley Institute): I’ve previously shared the audio recordings of this mini-course I taught for Holy Trinity Raleigh. St. Andrews Mt. Pleasant decided to one-up them and capture on video. These versions of the lectures are the fullest ones, as I was given a full seven hours of teaching time in total at St. Andrews, and they should be live soon on this page.

AI Customer Service? (WORLD Opinions): My latest for WORLD focuses on the growing industry of AI customer-service assistants—not just the text chat bots, but ones that answer the phone and do a better job than the frankly rather robotic humans we usually find ourselves talking to. Is this an example of a good use of AI, or an example of how modern technology is often called in to solve a problem it has itself first created?

On the Bookshelf

Stephen O. Presley, Cultural Sanctification: Engaging the World like the Early Church (2024): I’ve now finished this book, and gotta say I’m a bit underwhelmed. There’s nothing really to disagree with here, but perhaps that’s part of the problem. Every time he starts to wade into possibly contentious territory—for instance when talking about how the early Church tried to be very discerning about the vocations that Christians were allowed to serve in and those they were discouraged from—he pulls back from drawing any very concrete applications that might really ruffle feathers. Also, perhaps more significantly, the prose is just exceedingly mediocre throughout, although perhaps par for the course of most evangelical writing. I might even write something soon about the importance of good style, it’s got me so fired up. All that said, if you’re looking for a good primer on how the early Church transformed Roman culture and how we can learn from that today, it’s a pretty easy read and a good survey of the terrain.

D.C. Schindler, Freedom from Reality: The Diabolical Character of Modern Freedom (2017): FINALLY FINISHED! I’ve got to say this is one of the most intellectually exhausting books I can recall reading, but it was definitely worth the work and the journey. I’m still not at all sure what I think about it all, and will have to read the rest of Schindler’s trilogy I suppose (and then probably re-read the whole) before I can entirely make up my mind. But it will be a key touchstone of my thinking going forward, no doubt, and I may share some thoughts and reflections here over the coming months as I go back through and take notes.

Iain McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary (2009): I’ve more or less put this book on pause for the time being, as I’ve found that complex neuroscience is not generally what I’m in the mood for when trying to decompress on a commute or before going to sleep (the main times I listen to audiobooks). It’s all very interesting of course, but I needed something more narratival for a bit. Something like….

John Keegan, The First World War (2000): Christopher Clark’s The Sleepwalkers made such an impression on me that I found myself hankering for some more World War I history. But I also wondered if I shouldn’t learn more about World War II, which I’ve never studied that deeply. On the other hand, it seemed like what I really needed was to learn about interwar Germany and the rise of the Third Reich, which unfortunately see"ms to have some important lessons for us today. So I decided—why not all of the above? I’m planning an audiobook trilogy that will collectively tell the tragic saga of how the 20th century went off the rails: John Keegan’s The First World War; William Schirer’s Rise and Fall of the Third Reich; and then either Keegan’s or Martin Gilbert’s history of the Second World War. I’ve just gotten to the Battle of the Marne in this first book.

Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace: My new goal: finish by Christmas. *fingers crossed*

Recommended Reads

“How Congress Unleashed the Presidency” (Chris Demuth, WSJ): An excellent piece, in the spirit of Yuval Levin, reflecting on the larger trends that have led to a situation where we find absolutely everything seeming to hinge on the decision between two deeply flawed candidates. You cannot tell a story of executive overreach without telling a story of Congressional abdication.

“America On-the-line,” (Clare Morell, American Compass): My colleague Clare Morell has written a very important piece at American Compass on how the dopamine-fueled economy is undermining the foundations of a free market and a self-governing republic. A couple key quotes: “Users craving dopamine are not 'free people' or 'rational actor' making uncompelled transactions. And there is no free market without people who are free....So what to make of the unemployed 25-year-old young man who lives in his parents’ basement, playing video games all day online with strangers? Is he a free and rational actor?” “A society can function in the face of substance abuse and addiction among some small share of its population. It cannot accept choices and behaviors incompatible with human flourishing and the common good becoming the norm.”

Get Involved

If you like this Substack, please spread the word with others. For now, this Substack will be totally free, but if you like the work I’m doing, please consider donating to it here by supporting EPPC and mentioning my name in the Comments.

If you have any questions or comments or pushback on anything you read here today (or recommendations for research leads I might want to chase down), please email me (w.b.littlejohn@gmail.com). I can’t promise I’ll have time to reply to every email, but even if you don’t hear back from me, I’m sure I’ll benefit from hearing your thoughts and disagreements.

Somewhat related article from 'Public Discourse' today: https://www.thepublicdiscourse.com/2024/10/96256/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=technological-mediation-in-a-disembodied-world-a-review-of-christine-rosens-the-extinction-of-experience

I stopped watching movies (until they were extremely well vetted and I'm up all night on-call needing a few hours of mindless respite) about 30 years ago because the emotional manipulation always bothered me. Also I take very few photographs anymore because I'd rather just use my vision to enjoy the scene. I really appreciate the Amish approach here. Some real wisdom there.