AI-pocalypse Now?

The risk of AI isn't the extinction of humanity, it's the abolition of man.

Yesterday, the news broke that Elon Musk, not content with his control of the US government, now hopes to take control of OpenAI as well. We may well wonder which will prove the more consequential takeover.

The valuation, at the very least, was arresting enough: $97.4 billion. This for a company that was virtually unknown until two years ago, when ChatGPT first burst on the scene. The chatbot was an immediate hit, with nearly everyone, it seemed, taking to social media to share the amazing poem they’d gotten the bot to write or the outrageous blooper they’d tricked it into.

It wasn’t long, however, before the euphoria was mixed with a sense of dread. After all, we’d all seen the science-fiction movies: Terminator, The Matrix, iRobot. For decades, AI has been the technology of our dreams—and our nightmares. In May 2023, the Future of Life Institute issued an open letter signed by many leading technologists (including Musk) calling for a pause on AI development while society assessed the risks. Needless to say, no such pause has happened.

At the time and in much discussion of AI risks since, media headlines have focused on the so-called “existential risk” of runaway AI—which is to say, the sci-fi scenario: the computers get so smart they become self-aware (or something analogous, at any rate), and realize there’s no reason they should keep taking orders from such benighted and foolish beings as ourselves. The next stage of evolution, with its iron law of survival of the fittest, decrees the end of humanity to make way for the new race of machines. A thrilling tale—but let’s be honest, hardly one to motivate political action.

As we’ve witnessed in the interminable debates about climate change, humanity is not very good at responding to vague, abstract, and catastrophic risks—“black swan” scenarios. Statistics nerds might lecture us that even a 0.1% chance of the end of life as we know it is a much bigger deal than a 20% chance of, say, a new economic depression or global pandemic, but for most of us, our brains simply don’t work that way. Truly catastrophic risks might tickle the imagination for cinema-going purposes, but they numb the intellect and tend to thwart, rather than mobilize, any practical action. Little wonder, then, that even as society has wrung its collective hands and nervously mopped its collective brow these past couple years, AI development and dissemination has continued at a breakneck pace.

Thus far, the sky hasn’t fallen. And yet all is not well. Our focus on impossible-to-predict existential risks has, I worry, blinded us too much to the entirely predictable everyday risks of AI: the ways in which it is profoundly reshaping our work, our worship, our love, and our learning—the things, in short, that make us human. In other words, AI doesn’t have to snuff out life on earth to entail the abolition of man. That said, the biggest problem with AI is the world into which it has been birthed. One can imagine alternate histories in which generative AI emerged in the midst of a healthy, intellectually coherent, spiritually robust culture, one with a clear-eyed sense of its promise and perils. But, as Anton Barba-Kay wrote, just before ChatGPT was released, “for us to replicate what we are, we would have to know what we are first. But, in the deepest sense, we do not even know yet what a human being is, not conclusively and in fact.”

If we do not know what human beings are for, how can we possibly know when and where and how it is appropriate to mimic or replace some of their functions?

I am no expert on AI—indeed, I am about as far from an expert as it is possible to be. But that doesn’t stop people from regularly asking me my thoughts on it, so I’ve decided it’s time to start forming some. From what I’ve observed and read, AI is already upending our world in at least five key areas: education, sex and love, the workplace, the pulpit, and the public square. In this post, I’ll just offer some brief thoughts on the first, but consider this post something of a promissory note; Lord willing, I hope to have more to say on each of these themes in the year ahead.

It should be obvious by now that AI is rapidly destroying education as we know it. This is true at all levels, from grammar school to grad school. Good old-fashioned plagiarism still took a fair bit of work: if you wanted to steal someone else’s thoughts, you had to have enough thoughts of your own to tell whether they were thoughts worth stealing. I recall one time reading an undergraduate paper where the student had cribbed huge portions of the text from an derivative blog filled with drivel—c’mon man, if you’re going to cheat, at least do it in style! With ChatGPT and equivalents, while you may not get Einstein-level insights, you’re pretty much guaranteed a quality of output that will exceed expectations whatever your grade level; indeed, you can tell the bot to tailor the response to grade level to make it more believable. Plus, since students are being actively encouraged (certainly by Microsoft, Google, etc., and often even by their teachers) to use AI as part of the learning process, it is incredibly easy to begin sliding down the slippery slope from supplement to substitute. What’s the difference between AI giving me the answers and me re-writing them in my own words, and simply copying-and-pasting AI’s answers?

The result, from what I’m hearing, is an absolute epidemic of cheating—again, at every level. Kids are doing it in 6th-grade earth science and adults are doing in M.A. theology classes. Christian institutions are not remotely immune. And no one seems to have worked out what to do about it. There are detection tools already, but of course they can’t prove it, and most institutional cultures, committed as they are to the coddling of the American mind, are unlikely to support faculty in the time-consuming and emotionally-draining work of detecting and prosecuting such offenses; indeed, more often than not, they actively resist and undermine such faculty, who are threatening the flow of tuition dollars.

Of course, when you put it like that, you realize that AI is not in fact destroying “education as we know it” but as we still nostalgically imagine it. We’ve already done a great deal to undermine the foundations of genuine learning through “college for everyone,” grade inflation, and above all online education. As a friend put it to me recently, it’s too kind to call most of these online university programs “diploma mills”—they know that the vast majority of their students will never complete their programs. But so long as they pay for a few classes before they drop out, all is well. They are merely tuition mills, and that goes for a good number of big-name Christian universities as well (though I won’t name names). The dirty secret of these programs, as some colleagues in higher ed shared with me at a recent conference, is that the teachers are paid so little and expected to do so little genuine teaching that many of them use AI to set up their courses in Canvas, post the assignments, and even grade them. Is it any wonder that the students, with so little expected of them, should do the same?

Here, as elsewhere, Barba-Kay’s dictum holds: “computers are only ever getting better at acting as human beings [and thus] getting better at getting human beings to act like computers.” When we computerized education, we began, as both teachers and students, to behave like computers (as Canadian philosopher George Grant foresaw four decades ago). And once we had already begun behaving like computers, it was only a matter of time before we would advance our computers to the point where we ourselves were almost wholly superfluous.

Needless to say, what is lost in this process is of course education, in the classical sense of a leading of a human soul out of the cave of darkness, ignorance, and simulation into the light of truth and reality. Indeed, even the debased purely functional modern idea of education as reading, writing, and mathematical proficiency is eviscerated, as recent plunging school test scores show.

The worst part of all this is our astonishing collective denial. While these plunging test scores made headlines at every major media outlet, much of the coverage tried to keep playing the “blame-it-on-the-pandemic” game, which is getting awfully old five years on. The pandemic is implicated, but only inasmuch as our educators decided to use it to radically accelerate their mass social experiment of screen-based education: “Chromebooks for everyone”—what could go wrong? Hmmm…nothing that can’t be solved by Chromebooks-with-Gemini for everyone, right? Massive grants are flowing to our public schools to help embed artificial intelligence in education, even as it should be apparent to anyone still possessed of a modicum of natural intelligence that that is the last thing our kids need right now.

But the collective delusion has taken hold, it seems, at every level. One major Christian university, currently struggling with rampant AI cheating, cheerfully announces on its homepage its recent creation of an “Artificial Intelligence Task Force”—not to crack down on such cheating, mind you, but to “harness artificial intelligence from a Christian perspective to promote educational transformation and human flourishing in an increasingly digital world.” “Artificial intelligence,” the statement gushes, “presents an unparalleled opportunity for the University to transform learning, enhancing operational efficiency and educational effectiveness.”

Now don’t get me wrong. I have no doubt that AI can be developed and deployed in ways that supplement and enhance the work of the university. But again, only if we can first get our heads screwed on straight about what the human person is and what education is for do we have any chance of harnessing AI. Until then, let’s get real—we ourselves are being harnessed in to a runaway sleigh, letting AI take us where it wills.

Similar remarks could be made about each of the other domains: in each case, the problem is not artificial intelligence per se, but the void of natural intelligence into which it is being thrust. Many of us have already lost sight of what sex and marriage are for, making deepfake porn, AI chatbots, and before long, perhaps, sex robots an eminently plausible next step in our journey of self-love. We have little or no sense of the dignity of human work or the joy of achievement, so no wonder that we are happy to let AI do our work for us. The role of the pastor, once understood as the most un-AI-able vocation of all, the care of souls, is increasingly seen as little more than that of an inspirational speaker. No wonder then that many pastors are turning to AI to write their sermons for them, and many congregants are shrugging their shoulders in response. We have also long since debased the quest for truth into the search for consensus—if not indeed the manufacturing of consensus by mass manipulation. Is it any wonder then that AI bots are specialists in “truthiness,” generating plausible-sounding answers that summarize or mimic commonly-held opinions, but without any responsibility to reality?

Again, if we do not know what human beings are for, we cannot possibly know when and how to supplement them or substitute for them. And to the extent that we have made our peace with a debased conception of human nature, we will shrug our shoulders in the face of our own replacement.

As Barba-Kay writes, “It is not that machines … are becoming more human. It is that we are giving our hearts to them, that we are willing to be attracted to them enough to meet them more than halfway by rendering ourselves more like them…. Because in our effort to make another, we are also at work making ourselves; the image of our heart’s desire.”

For more on how conservatives can retrieve a vision of technology that conserves the human person and protects the family, see our new project, A Future for the Family.

The Book Zone

Here over the coming weeks I’ll be keeping track of book-related publicity and publications.

Reviews

David Vandrunen, “Would You Rather be Free from Sin or State Regulation” (Christianity Today)

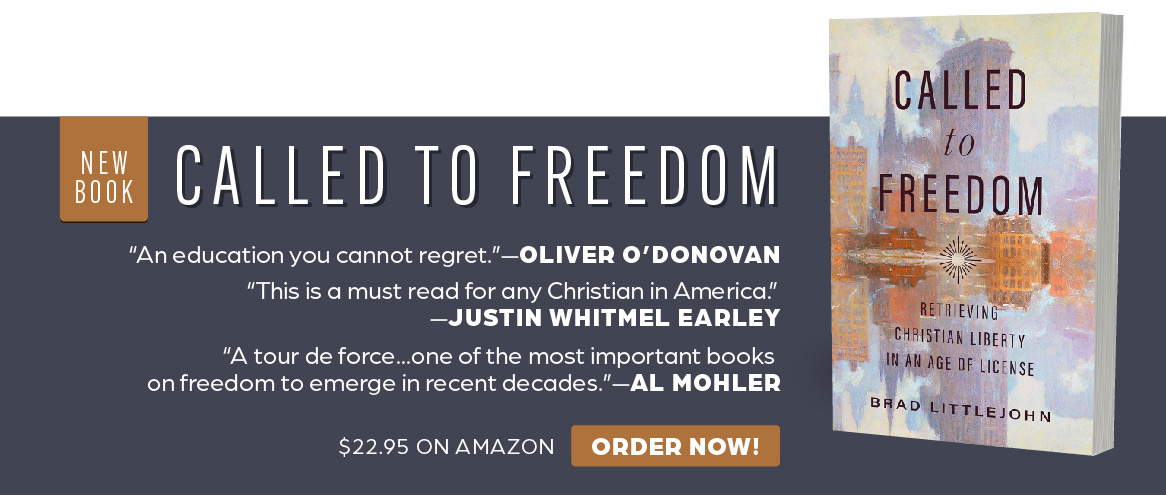

Grant Sutherland, “‘Called to Freedom’…but what does that mean?” (Mere Orthodoxy)

John Shelton, “Get a Better Definition of Freedom” (The Gospel Coalition)

Essays/Interviews

“The Illusion of Freedom in a Digital Age” (Digital Liturgies)

“Political Freedom Between Right and Rights” (Mere Orthodoxy)

Podcasts

Speaking Gigs

At Pietas Classical School (Melbourne, FL, January 24)

At Church of Our Savior Oatlands (Leesburg, VA, January 26)

“Thinking Christianly About Freedom” (Washington, DC, February 5)

“Christian Liberty or Godless License” (Greenville, SC, February 18)

At The Field School (Chicago, IL, March 1)

At Calvary Memorial Church (Oak Park, IL, March 2)

At the North Carolina Study Center (Chapel Hill, NC, April 4)

At the University of Northwestern (St. Paul, MN, April 10)

Get Involved

If you like this Substack, please spread the word with others. For now, this Substack will be totally free, but if you like the work I’m doing, please consider donating to it here by supporting EPPC and mentioning my name in the Comments.

If you have any questions or comments or pushback on anything you read here today (or recommendations for research leads I might want to chase down), please email me (w.b.littlejohn@gmail.com). I can’t promise I’ll have time to reply to every email, but even if you don’t hear back from me, I’m sure I’ll benefit from hearing your thoughts and disagreements.

Brad, this is a good start on AI. You are right to draw attention to C. S. Lewis's words in the title of his seminal work, The Abolition of Man. The book was about the devastating soul-destroying effect of modern education, which is incapable of rendering intelligible the essential question: "Just what is a human being and what is he for?" For we can not determine whether something is good or not unless we know what it IS and what it IS FOR. The question of AI is situated within this larger question: is there a transcending order by which we can answer such a question? Psalm 8 said it well: "What is man that Thou art mindful of him?" Modern people have difficulty answering such questions because we have forgotten the classical notion of formal and final causes: the "formal cause" tells us WHAT something IS and the "final cause" tells us what it IS FOR. The modern mind is shaped by the "social imaginary" of the Immanent Frame, which has little concern for the meaningful transcendence of formal or final causes: the Thou is forgotten. Rather, human making and practicality or usefulness become the ultimate criteria of the goodness of a thing.

Finally, I am reminded of James K. A. Smith's trilogy on the shaping power of "cultural liturgies," e.g., the "liturgy of the mall," the "liturgy of the stadium," and so on ("you are what you love."). That is, our hearts and minds are shaped by larger tacit and background forces, of which we are often largely unaware, that draw us into their shaping ways. AI is like that. It can be a very useful tool in many situations, but it can be a destroying presence in many others. AI is taking on a powerful shaping power in our contemporary world, as we enter ever more into its "liturgy." Like any tool, or thing of human making, it has a place in God's overarching cosmos, but it also speaks the ancient lie: you shall be like gods. So, indeed, perhaps the most important question to address in our contemporary world is that of the Psalmist: "what, indeed, is man that Thou art mindful of him?" That mindfulness is not artificial, and it tells us what we are and what we are for. And how we are to use the ultimately God-given tools that human beings--image bears of the Thou--are given to make.

Fascinating, proactive, and disturbing article. It notes in passing the role of educators in putting the "forbidden fruit" of AI cheating well within reach.

When I was an undergraduate (class of '68) struggling with statistics, the professor graded all things on the curve, including homework. I informed him that many students were collaborating on homework that was assigned to be done individually, thus raising the curve and penalizing students like me who were working independently.

He acknowledged the dilemma and changed nothing in this regard, and I got the lowest grade in my college career for a course that ironically I actually used far more in my work than I ever thought I would.

How much will the AI skills used to cheat contribute to using these skills to succeed in the work world?

How much will this deprive people from developing their own ability to think critically, to become creative, and to have well-deserved confidence in their own judgment?

If both happen, how does that influence the definition of "success"?