In a recent feature for the Wall Street Journal, reporter Rachel Wolfe asked, “What Happens When a Whole Generation Never Grows Up?” Chronicling the growing trend of millennials and Gen Zs who never marry, never have children, and in many cases, never even leave home, the article told the story of Renata Leo, who at age 31 is still sleeping in her childhood bedroom, complete with unicorn wallpaper. While Renata told the reporter “I feel like a failure,” her parents liked to think they were helping her by giving her time to find a dream career: “Renata’s parents … say they want their daughter to have the freedom to pursue the life she wants rather than feeling, like they did, that she should submit to any job as long as it pays something.”

An even more depressing recent New York Times article, “The Unspoken Grief of Never Becoming a Grandparent,” highlighted the experience of a growing number of Baby Boomers coming to terms with their children’s decision to never have kids of their own. Although genuinely grieved, they all seem convinced that this is the just and proper price of giving their children freedom: “Like every parent interviewed for this article, Jill Perry, 69, said her two daughters — both in their 30s and child-free — should be able to make their own choices about parenthood, and they have her full support.”

But what if that’s not what freedom is all about? After all, we won’t live forever. “Keeping your options open” sounds great when you’re 20, or maybe even 30, and not sure you’re ready to settle down and have kids. But pretty soon, biology will start closing down your options for you. Our modern creed of freedom as endless optionality is not one for mere mortals. God did give us freedom to choose, but it’s of no use to us unless we actually choose—which is to say, commit ourselves to one path rather than holding all open as possibilities. Chesterton once said, “The purpose of an open mind is the same as that of an open mouth—it’s meant to close on something.” We could say something similar for freedom generally: our freedom is meant to find its end in another.

Our freedom to marry must terminate in a commitment to “have and to hold” one spouse; if we want to keep the freedom of singleness within marriage, we won’t experience authentic marriage at all. No wonder, then, that, deluded about freedom so many today are choosing not to marry—or if they marry, to keep open the option of an “open marriage” or divorce. Our regime of “reproductive rights” follows the same logic. Since it is still culturally unacceptable to abandon a child in the way we have normalized abandoning a spouse, more and more men and women of my generation are fearful of bringing a child into the world, using contraception and abortion to postpone this irrevocable commitment until it’s too late.

On the other hand, technology now stands ready to serve, helping every couple keep their options of childbearing open through IVF and surrogacy. Thanks to these miracles of modern science, two men can become “fathers” together, or a single celebrity woman who wants to keep her perfect figure can hire out a poorer woman’s womb to bear a child for her. We have quickly arrived at the dystopia that Oliver O’Donovan predicted four decades ago in Begotten or Made?: “Humanity will be made under contract, with all the component parts legally conveyable.” In the name of freedom, we have turned our technologies against our own humanity, putting us far down the road to what C.S. Lewis called “the abolition of man.”

The paradox of modern freedom is evident also in our digital technologies, which more than anything else hold out the promise of “anything you want, whenever you want it, no strings attached.” Not only does the digital realm open up limitless options to us, quite literally “on demand,” but unlike the real world, it enables us to have our cake and eat it too, to keep our options open by always reserving the chance to opt out of whatever we opt into: for every click, there’s a “back” button, for every “subscribe,” there’s an “unsubscribe,” for every “follow,” there’s a “block.” Again, though, our minds were made to close on something; confronted with absolutely endless options, we feel not freed, but paralyzed. How many times have you stared at the Netflix homepage and found yourself scrolling mindlessly, unable to pick a film? Perhaps less in recent years, as Netflix has learned that we want to be told what to watch; its algorithms do the picking for us. More and more, we find ourselves feeling the oppressive weight of digital freedom by trying to close off our options: apps with names like “Freedom” promise to shut down your web browser or smartphone for set periods of time so that you can escape addictive distractions. Freedom, it turns out, requires limits.

St. Paul would not have been surprised. After declaring our miraculous liberation from sin by the power of the Spirit, he calls on us to become “slaves of righteousness” (Rom. 6:18) and “bondservants of Christ” (Eph. 6:6). After his most extended reflection on freedom and slavery in Galatians, he declares, “For you were called to freedom, brothers. Only do not use your freedom as an opportunity for the flesh, but through love serve one another” (Gal. 5:13; note that the Greek word “serve” is the verb form of “slave”). It turns out that bondage of some kind is inescapable. We will all serve somebody or something. It is only a question of whom and how. Some forms of service turn out to be liberating, while some forms of purported freedom turn out to be enslaving and dehumanizing.

Today, we have pursued a vision of freedom that is afraid to be tied down by anything—by God, by other people, by human nature itself. The result is increasingly that we find ourselves empty, lonely, and paralyzed—and at the mercy of anyone ready to profit from our restless cravings, as the surging profits of the pornography and sports gambling industries show. It turns out that the political and economic freedom we’ve been taught to value—being able to make up our own minds and choose our own rulers—only makes sense for a people who are actually able to think and to choose, people who have cultivated the moral freedom of governing themselves and restraining their impulses. And this moral freedom is only fully possible for a people who have been given the spiritual freedom to rest their restless hearts in God, and for a culture that has been shaped and leavened by that spiritual freedom, as ours once was.

This is why I wrote Called to Freedom: Retrieving Christian Liberty in an Age of License: to provide today’s Christians with a clearer vision of what true freedom looks like, and how to recover it from the ensnaring false promises of which the Apostle Peter warned, “They promise them freedom, but they themselves are slaves of corruption. For whatever overcomes a person, to that he is enslaved” (2 Pet. 2:19). Today, we think ourselves the freest people the world has ever known, yet find ourselves among the most enslaved. I hope you will buy the book, read it with your family, and discuss it with your pastor and your friends. It doesn’t have all the answers, but it does try to frame the questions that Christians should be asking of our churches, our leaders, our technologies, and our economies. As John Jay wrote on the cusp of the Constitutional Convention in 1786, “It is time for our people to distinguish more accurately than they seem to do between liberty and licentiousness.” How much more would he say so today! The stakes for our families, our churches, and our nation could not be higher.

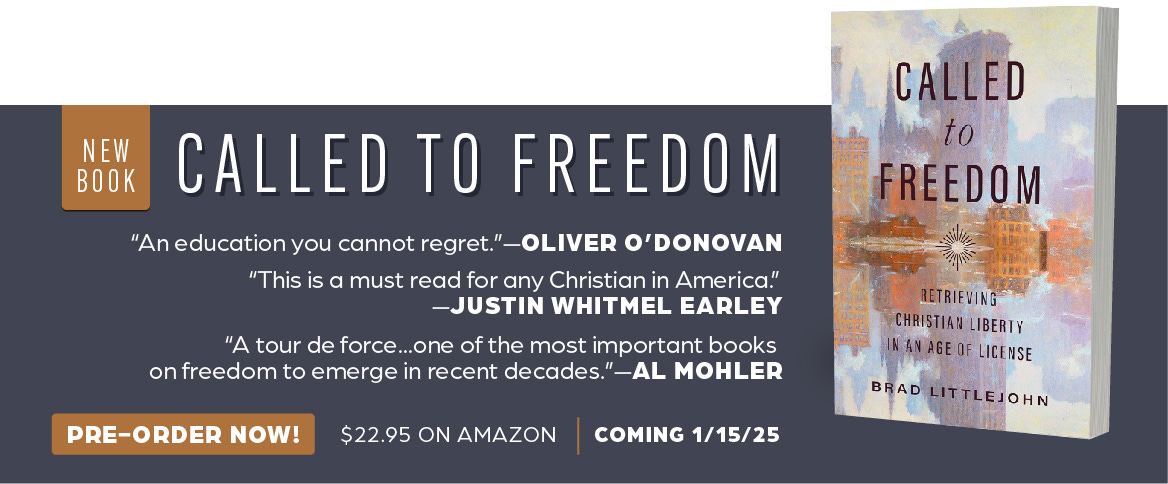

Today, the book releases at online bookstores everywhere (and maybe a few brick-and-mortar ones too). You can get it direct from the publisher, B&H, here, or via Amazon here. I’ve been very honored by the response the book has received thus far. Here’s just a few of the official endorsements:

“Called to Freedom is a tour de force and a much-needed consideration of freedom as defined by Christianity. Brad Littlejohn’s new book represents one of the most important books on freedom to emerge in recent decades.”—Al Mohler

“The joy of reading a clear thinker is that you start thinking clearly yourself, and how badly does America need clear thinking on the topic of what freedom means. This is a must read for any Christian in America.”—Justin Whitmel Earley

“Americans love freedom, but many of us embrace profoundly warped understandings of spiritual, moral, and political liberty….Every Christian family should buy a copy of this book, read it together, and discuss its implications.”—Mark David Hall

“How can the concept of freedom be recovered from the wreckage of contemporary rhetoric? … This is a book to make you more hopeful about that possibility, and yet more aware of the discrimination and thoughtfulness it requires. … It will be an education you cannot regret.” –Oliver O’Donovan

I do hope you’ll enjoy it just as much. Buy a copy, leave a review, and share with your pastor, friends, or family!

Get Involved

If you like this Substack, please spread the word with others. For now, this Substack will be totally free, but if you like the work I’m doing, please consider donating to it here by supporting EPPC and mentioning my name in the Comments.

If you have any questions or comments or pushback on anything you read here today (or recommendations for research leads I might want to chase down), please email me (w.b.littlejohn@gmail.com). I can’t promise I’ll have time to reply to every email, but even if you don’t hear back from me, I’m sure I’ll benefit from hearing your thoughts and disagreements.