In Defense of Childhood

Why Wednesday's Supreme Court hearing could change the internet as we know it

Let me start off with a ridiculously bold statement: January 15, 2025 could turn out to be a pivotal day in the entire history of the internet.

Now, let me defend it by giving some backstory.

If you stop to think about it, one of the critical differences between the physical world and the digital world is that the former has boundaries; the latter, by and large, does not. In the physical world, if you want to attend a concert or buy a rare book, you’ll have to travel to the location and get in through the door, which might be difficult if there’s a bouncer or you’re outside of business hours. However, you can access a website from anywhere, at any time—and generally, whatever your age. This last has been perhaps the most culturally significant feature of the internet. The very possibility of maintaining a culture and a civilization depends upon a society’s ability to maintain the boundaries between childhood and adulthood.

In traditional cultures, there were formal rituals marking this basic boundary, and your life was radically different before and after you passed that boundary: there were certain places that only adults could go, certain conversations only adults could be a part of, and certain activities only adults could engage in. [Edit: Since writing this, I’ve started reading Neil Postman’s The Disappearance of Childhood. He has convinced me that the above statements are too strong—that much of what we now consider “childhood” vs. “adulthood” is less than 500 years old—although I think his own case is also too strong, and he ignores parallels in more traditional cultures. That said, Postman and I agree that civilization *as we know it*, with its many blessings, depends on this distinction, and we lose it at our peril.] With modernity, some of the formality and ceremony of these rituals broke down, but in their place, laws were codified defining the age of consent for marriage and sexual activity, the minimum age for voting, buying alcohol, tobacco, or firearms, and much more.

The very possibility of maintaining a culture and a civilization depends upon a society’s ability to maintain the boundaries between childhood and adulthood.

For most of the 20th century, childhood was certainly quite different from what it had been in traditional societies, but it was still childhood—something clearly distinct from adulthood. Because young humans, like young plants or animals, are fragile while still developing, we shelter and support them in special ways, to increase their chance of emerging into adulthood strong and mature. In other words, if we cannot guard childhood as childhood, neither will we have adulthood as we have known it, and as civilization requires it: fully-developed agents capable of restraining their desires, making commitments and following through on them, and distinguishing fantasy from reality.

In the early days of the internet, Congress, recognizing the civilizational importance of childhood, tried to take steps to ensure that this new virtual world developed with some semblance to the physical world, by requiring the creation of age-gated spaces. The first such attempt, the Communications Decency Act of 1996, was fairly ill-conceived and was struck down the following year by the Supreme Court for various vague and overbroad provisions. However, in a concurring opinion, Justice O’Connor noted that the basic aspiration behind the law was laudable and that, as soon as the technology could catch up, it would be desirable “to construct barriers in cyberspace and use them to screen for identity, making cyberspace more like the physical world and, consequently, more amenable to zoning laws.”

Although optimistic that this “transformation of cyberspace was already underway” in 1997, Justice O’Connor failed to realize that without strong legal nudging, the incentive structures for the burgeoning internet industry pointed all in the other direction: the fewer barriers to the flow of people, information, and yes, pornography around the internet, the more money there was to be made. Thus, when a second Congressional effort, the Children’s Online Protection Act of 1998, finally made its way to the Supreme Court in 2004, the Court deemed, in a narrow 5-4 decision, that the technology still was not suitable for age verification, which would impose such a privacy and security burden on adult users that it raised First Amendment concerns and could not be upheld.

For the next two decades, the internet developed along a radically different track from the physical world—an unbounded, largely unregulated space where children could, absent highly engaged parental supervision, participate in adult conversations and activities.

The result was that, for the next two decades, the internet developed along a radically different track from the physical world—an unbounded, largely unregulated space where children could, absent highly engaged parental supervision, participate in adult conversations and activities. This might not have been so terrible if the digital world itself had remained an enclosed realm that was hard to enter, as it had been in the 1990s. But with the advent of smartphones in 2007, and many parents’ short-sighted rush to purchase them, any barrier between digital and physical worlds came crashing down in a hurry. The result? Jonathan Haidt calls it a “screen-based childhood,” but that is a misnomer. For it wasn’t a childhood at all, a concept that, as we have seen, presumes boundaries between child and adult experiences. Children were, instead, immediately accelerated into the adult world—whether the merely disorienting and overwhelming networks of social media, or the darkest and most disturbing corners of the adult world, like online pornography. As a result, they were robbed of childhood—their brains, unprepared for such experiences, were hijacked and their development stunted.

For the past three years, a new movement in defense of childhood has exploded onto the scene. We have realized that the only way to protect it is to force the digital realm to begin to roughly mimic the kinds of boundaries between adult and child spaces and experiences that exist in the physical world. The technology industry has fought back tooth and nail, recognizing that its massive profit margins depend on addicting customers when they’re young, and maintaining a maximally frictionless experience for all ages. No industry has fought harder than the pornography industry, which fought one such law, Texas’s HB 1181, all the way to the Supreme Court.

That is why this Wednesday’s showdown was so important. At stake was not just one law, nor indeed just the 18 other similar state laws, nor indeed merely minors’ access to online pornography. At stake was a principle: can we start zoning the internet to protect childhood?

At stake was not just one law, nor indeed just the 18 other similar state laws, nor indeed merely minors’ access to online pornography. At stake was a principle: can we start zoning the internet to protect childhood?

The case before the Court

Of course, as often in law, a big principle presented itself in a very narrow form. Technically, the question before the court was only this: what is the appropriate standard of review for evaluating a preliminary injunction against the law? The porn industry (Free Speech Coalition) had filed what’s known as a “facial challenge” to the law, insisting that it was unconstitutional on its face and therefore should be prevented from going into effect, without waiting for any party to be concretely harmed by it. That’s quite a bold claim, but somewhat surprisingly, the District Court bought it, and issued a preliminary injunction barring the law from going into effect. On appeal to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, Texas succeeded in getting that injunction overturned.

But what was most interesting (and surprising to most legal analysts) about the Fifth Circuit’s decision was how they arrived at that conclusion. They decided that it was barely even a question; of course Texas had a right to require age verification for pornography. After all, minors had no constitutional right to such material, and although age verification might be a bit of an inconvenience for adults, it hardly amounted to a meaningful “burden” on their access to speech. (Truthfully, adults have no constitutional right to access most of this material either, but that is a battle for another day.) Thus, the law only had to meet the broad standard of “rational basis,” as did similar age-gating laws on brick-and-mortar businesses. In the 2004 Ashcroft decision, the Court had ruled that age verification did meaningfully burden adult access, and thus triggered “strict scrutiny”—a burden that can only be met by showing that there is no other “less restrictive means” of achieving the “compelling government interest.” The porn industry has always maintained that parental control software was a less restrictive but perfectly adequate means of getting the job done, an argument that five Supreme Court justices bought in 2004.

There were thus two ways Texas could convince the Supreme Court to uphold its law. Either it could get the high court to agree in applying rational basis review, which would make the law easy-peasy, or, even if the Court slapped down the Fifth Circuit’s “rational basis” standard, it could still determine that parental controls were no longer sufficiently effective to be treated as an alternative, “less restrictive means.” (This latter was what Clare Morell and I argued in our amicus brief to the Court and our recent lead article in First Things).

That said, most veteran legal observers took a dim view of both prospects. Many believed that the Court would be very unlikely to uphold rational basis, deferring instead to a string of precedents from an earlier technological era that saw online age verification as a serious burden that triggered strict scrutiny. And they pointed out that the Court almost never upholds laws under strict scrutiny, which is often seen as a death sentence. Even the more sanguine analysts thought that the likely best-case scenario would be one in which the Court simply kicked the can down the road: it would probably remand the case to the Fifth Circuit with instructions that it needed to re-evaluate the law under strict scrutiny, and possibly hear it again after renewed appeal in a couple of years. However, our coalition hoped that at least in such a case, several justices might indicate that they would be inclined to uphold the law under strict scrutiny in a subsequent appeal.

What happened on Wednesday

What actually happened surprised all of us. From start to close of oral arguments, which lasted over two hours, the porn industry was on the back foot, with their attorney, Derek Schaffer, enduring a barrage of criticism from seven of the nine justices. Then the Deputy SG of the United States had the opportunity to present the Government’s view on the law, which was essentially that while strict scrutiny should probably be applied, the law was urgently necessary to protect children from porn and the Court should indeed make clear to the Fifth Circuit that it would be inclined to uphold the law under strict scrutiny. The justices all seemed quite amenable to this, with several hinting, however, that they thought this approach overly conservative—if brick-and-mortar age verification wasn’t subject to strict scrutiny, why should online age verification? Finally, when Texas SG Aaron Nielson spoke, he faced mainly technical questions about how exactly the law was designed to operate and how age verification worked, and was encouraged to make sure that some of those details were firmed up when the law was actually enforced.

Strikingly:

Not a single justice questioned that youth porn exposure is a public health crisis requiring urgent government action. The porn industry’s line throughout this litigation has been that, while of course kids probably shouldn’t watch this stuff, there’s no evidence at all of serious mental health issues related to it, and that talk of “porn addiction” is fanciful pseudo-science. The District Court judge, meanwhile, had seemed to accept that the pornography in question consisted of little more than R-rated movies on Netflix. I didn’t hear a single Supreme Court justice buying these ridiculous lines.

Not a single justice seemed interested in the porn lobby's argument that “content filtering”/parental controls can get the job done just fine. The very first questions, from Amy Coney Barrett and Justice Alito, made mincemeat of those claims, and content filters were barely mentioned again after the first five minutes. This is really quite extraordinary, given how large filters loomed in the Ashcroft majority decision and the fact that the porn industry has made them the centerpiece of its argument: “by all means protect kids, but parents can do that just fine with existing software.” Most parents know better, and thank goodness, so do the justices it seems.

Many justices openly acknowledged that rapid technological change calls for reconsideration of precedent, with Chief Justice John Roberts perhaps being most explicit on this subject. Again, this seems obvious to many of us, but the Court has generally been very hesitant to revisit precedent and has sometimes seemed a bit oblivious to the rapidly-changing technological realities. Not anymore.

Therefore, all the justices seemed to think some kind of AV legislation should be able to survive constitutional scrutiny; and at least seven of the justices seemed to think that the current form of the TX law (and similar laws in 18 other states) probably did so.

Thus the only real question in the room was “how do we fit this into the rather conflicted precedent on this issue?” Should rational basis be applied, reversing precedent but bringing the digital world in line with the jurisprudence governing the physical world? Or should they stick with “strict scrutiny” but make clear that it’s not quite so strict after all at least when it comes to this issue. On this question, justices Jackson and Sotomayor definitely seemed concerned to uphold the strict scrutiny standard, Kagan and Barrett less clear, and the other five justices perhaps open to applying a looser standard (rational basis or the rarely-used “intermediate scrutiny”).

Either way, though, there seemed to be a clear majority in favor of upholding the right of Texas and other laws to impose age verification on porn sites (and perhaps by extension, other forms of media destructive to children). The only questions then is whether it would be a green light (rational basis) or a yellow light (strict scrutiny), and whether the Court would just settle the question for itself, closing the case, or send it to the Fifth Circuit with instructions. It’s a bit more complicated than that, in terms of the various procedural options open to the Court, but I’ll leave those aside given the limits of my own expertise and of readers’ interest.

Nothing is certain, of course; we will have to wait for the justices’ opinions, and should pray for wisdom and a good result. The upshot, however, is this: It seems very likely that the Court will soon hand down a judgement making clear that states will have meaningful room to maneuver on age-zoning the internet from this day forward, for the first time in at least three decades—that is, since America first started going online. A pivotal day in the history of the internet, and a pivotal day in the battle to defend childhood—which is to say, to defend the very future of our society.

Praise God from whom all blessings flow!

If you’re interested in the blow-by-blow, check out my live-tweet thread from oral arguments, or the far more expert thread of my colleague Ed Whelan.

Watch my Speech from the Rally!

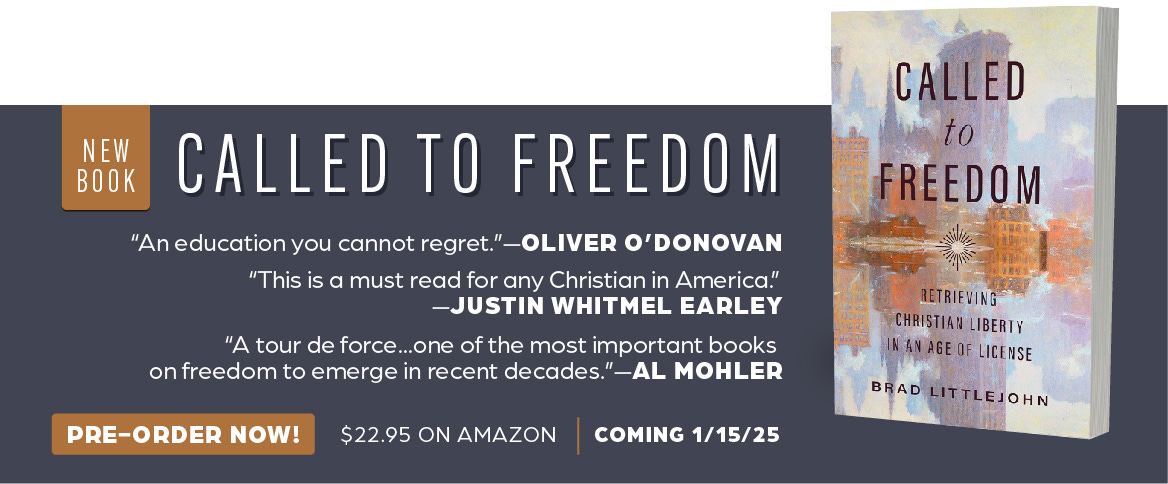

Called to Freedom is Out…and Making a Buzz

On the same day as oral arguments, which featured the licentious porn industry opposing the freedom of Texas to protect its children, my book Called to Freedom: Retrieving Christian Liberty in an Age of License was released! It’s been racking up five-star reviews on Amazon and the first official review, in Christianity Today, was published today by my one-time nemesis (though a true gentleman and a scholar), David VanDrunen.

If you want to get more of a taste of the book before buying, check out these guest posts:

“The Illusion of Freedom in a Digital Age” (Digital Liturgies)

“Political Freedom Between Right and Rights” (Mere Orthodoxy)

Or, if you’re the podcasting type, you’ve got a lot of options now if you’d like to hear about the book:

Get Involved

If you like this Substack, please spread the word with others. For now, this Substack will be totally free, but if you like the work I’m doing, please consider donating to it here by supporting EPPC and mentioning my name in the Comments.

If you have any questions or comments or pushback on anything you read here today (or recommendations for research leads I might want to chase down), please email me (w.b.littlejohn@gmail.com). I can’t promise I’ll have time to reply to every email, but even if you don’t hear back from me, I’m sure I’ll benefit from hearing your thoughts and disagreements.