Live Not by (Your Own) Lies

Conservatives have been warned against the reality-distortion filter coming from the Left--but are we as attuned to our own self-deceptions?

Most of you reading this are probably familiar with at least the title of Rod Dreher’s recent book, Live Not by Lies. I confess I’ve not yet read it myself, but I’ve heard him speak on it, and it sounds like an important and powerful reminder not to lose your bearings on reality, and the courage to name the world rightly, in an increasingly post-truth society. His particular concern is the ideologies of the contemporary Left, which he sees adopting a slightly more subtle and sophisticated version of the tactics of totalitarian communism last century. By changing the meanings of words and repeating falsehoods brazenly and insistently, it creates an environment in which many lose their grip on reality and see the world the way the ideologues want them to, and in which even those who know better become so jaded and demoralized that they see little point in speaking truth, or wonder whether there even is such a thing.

While this evil is real and undeniable, as a conservative I find myself more concerned about the ways in which the Right, too, has learned to live by lies. This happens in several different ways. Sometimes, it is pure Machiavellianism: the stakes are higher, we need to gain power, the other side is willing to play dirty, and so we should too. Most Christians, at least, won’t consciously adopt that justification for lying, although some may gesture toward Rahab and the Hebrew midwives as examples of godly deception to be followed in times when politics has broken down into war by other means, as they claim it has today.

More common, though, is I think a much more subtle justification, which I came across in a post by Baptist theologian J.D. Greear today:

“In his critique of the American left, Shelby Steele laments a concept he calls “poetic truth,” by which he means the propensity of the left to misconstrue facts or selectively report evidence in order to affirm a truth they believe is more true than even the facts themselves. Strangely, he says, dispensers of poetic truth feel justified in their distortions because they know the bigger narrative is true even if not all the facts support this particular case.”

Although we are all familiar enough with this tactic from left-leaning journalists, Greear observes, with good justification, that “this impulse is just as seductive to those of us on the right, too.” Since at least 2020, I’ve observed this growing tendency among many friends I used to see eye-to-eye with and thinkers I used to respect. Searching for certainty and clarity in an increasingly chaotic world, we try to connect the few dots we see (or we think we see) into a Narrative. The Narrative makes sense of things—it explains a bunch of seemingly disparate phenomena, it accounts for unpleasant experiences we’ve had, it gives us the satisfying clarity of Good Guys and Bad Guys, and best of all, it supplies plausible motivations for the actions of the Bad Guys.

The Narrative makes so much sense of so many things that, once it comes into focus for us, it just feels true. Mistaking coherence for correspondence to reality, explanatory power for facticity, we know it must be true. Armed with the Narrative, we set out to connect more dots, and explain more phenomena. When we find an inconvenient number of data points that just don’t seem to fit, we convince ourselves that that’s exactly what we should expect if the Narrative were in fact true—of course the Bad Guys would cover their tracks and sweeten their words with plausible deniability. Thus, we come to take the non-correspondence of the facts as further proof of the Narrative—not realizing that in doing so, we have rendered the Narrative completely unfalsifiable, and locked ourselves within a sealed epistemic capsule. When we go to share the Narrative with others, however, we worry that they, not yet being True Believers, may be overly swayed by those pesky facts which don’t seem to conform. Accordingly, we shade or slant the truth, distorting the facts and lying about others, and convincing ourselves all the while that these lies are more true—in a poetic sense, at least—than the facts themselves.

This seduction is powerful enough for individuals on their own—but put them in social settings where they feel expected to produce a certain narrative, and it is all but irresistible. A delightful passage in War and Peace illustrates vividly. Asked to recount a battle he was part of, a young man ends up finding himself spinning a story far more dramatic and heroic than the sordid and confused affair he actually experience.

“Rostov was a truthful young man; he would not have intentionally told a lie. He began with the intention of telling everything precisely as it had happened, but imperceptibly, unconsciously, and inevitably he passed into falsehood….To tell the truth is a very difficult thing; and young people are rarely capable of it. His listeners expected to hear how he had been all on fire with excitement, had forgotten himself, had flown like a tempest on the enemy’s square, had cut his way into it, hewing men down right and left, how a sabre had been thrust into his flesh, how he had fallen unconscious, and so on. And [so] he described all that.”

Asked to give a graduation address this spring for a classical high school, I quoted this passage in the course of an exhortation to the students on the temptations to untruthfulness that peer pressure creates—and all the more so in a digital age of in which truthfulness must so often give way to the demands of virality. I went on to say:

Of course, as Tolstoy well-understood, we lie to others in part because they lie to us—through flattery. Scripture warns us constantly against the dangers of the flatterer, warnings we would do well to heed in our hyper-networked age. Flattery, though, takes many forms. The young men here may think they are invulnerable to it, but it’s just not just people on Instagram telling you how beautiful you are. Flattery happens whenever people tell you what you want to hear, rather than what you need to hear. When someone makes a political meme that gets you to smile and nod, “Yes, those people are idiots,” you’re the victim of flattery. When someone posts something calculated to get you to indulge in cathartic rage, rather than rational thought, you’re the victim of flattery. Whenever someone retweets your dumb hot-take because it reinforces their own, you’re the victim of flattery. Beware of anyone who flatters you by confirming what you already think rather than challenging your assumptions, by preaching to the choir while pretending to be a courageous prophet.

Look instead for the voices in your life that unsettle you and make you feel a bit uncomfortable, and force yourself to spend some time around them. You don’t have to live in that space—especially in such a mixed-up world, we do need people who will confirm our sense of reality if we’re not going to go insane—but don’t cut yourself off from genuinely contrarian voices.

(You can read the whole address here.)

In his Cassandra-like diagnosis of American society’s near-terminal condition, Democracy and Solidarity, James Davison Hunter worries about nothing so much as our mutual collapse of confidence in truth and commitment to truth-telling. Each of us now assumes we are being lied to and so sees little reason to trouble too much over the truthfulness of our own statements. But, he warns, “a post-truth democracy is a contradiction in terms. It would mean that a nation is ungovernable.”

If there is any silver lining here, it is this: light will shine brighter as the darkness around it deepens; likewise, Christian witness can shine out more clearly the rarer and more countercultural it is. We have good reason to doubt just how much Christian political action can achieve in a post-Christian society: will we be able to do much to protect the unborn, or incentivize child-bearing, or stabilize the now-fluid concept of gender? Perhaps so; perhaps not. We can, however, commit to doing something truly and transformationally counter-cultural: to refuse to live by lies—not just those of others, but our own as well.

Newly Published

“The Anti-Human Future of AI”: You know that maddening Olympics ad for Google’s Gemini? The one where the dad asks AI to write a fan letter from his young daughter to her favorite athlete? It tells us a lot about how AI’s boosters think about humanity and the role of technology. We must resist their anti-human future if we don’t want to end up like the slurpee-sipping humans in WALL-E, I argue in my latest WORLD Opinions column.

I also recorded a radio version of this column for “The World and Everything in It,” which you can listen to on today’s episode.

Coming down the Pipe

Review of Democracy and Solidarity: I just submitted my review of James Davison Hunter’s magisterial new book to University Bookman. I’ve been commenting on the book in this space as I’ve been reading it over the last few weeks, and you’ll probably be hearing a lot more from me on it—I’ll also be contributing to a symposium on it at Mere Orthodoxy. It is one of the most important books of recent years and a must-read for anyone on Left or Right (or center, if there still is such a thing!) committed to shoring up the foundations of our republic. Here’s a passage quite relevant to today’s post:

“[Our] shared cultural logic is defined by a moral authority rooted in rage, anger, and often hatred. Its mythoi or collective self-understandings revolve around narratives of injury and wounded. Its ethical dispositions are defined by the desire for revenge through a predilection to negate. Its anthropology effectively reduces fellow citizens to enemies whose very presence represents an existential threat. And its teloi are power oriented to domination.”“Phone Bans and Parental Choice”: I’ve just written a piece for the Institute for Family Studies blog that should publish next Monday, extending some of my thoughts on freedom from last week’s Substack. The biggest obstacles to common-sense smartphone policy among conservatives, I suggest, are appeals to “consumer choice” or “parental choice” that fail to realize the extent to which freedom is a property of communities. The truest freedoms, I argue, are found in forms of collective action.

“How to Be Pro-Life in a Pro-Choice World”: I’m told this piece will publish this week at WORLD Opinions. In it, I consider how pro-life conservatives should respond to the new political reality, lacking for the first time in decades a national party committed to their cause. “Depressing as this moment may seem,” I write, “we can at least be grateful for the clarity it provides: you cannot have a pro-life politics without a pro-life culture.”

Politics and Faithful Citizenship mini-course: This weekend, I’ll be teaching the first iteration of a mini-course for churches on how to think about politics, government, law, and citizenship through a theological lens. I’ll be teaching it initially at Holy Trinity Raleigh (ACNA), at the gracious invitation of John Yates III. Later on, I’ll be teaching at St. Andrews Anglican, Mt. Pleasant (ACNA), September 13-14; and City Church of Richmond (PCA), September 20-21. If you live near one of these churches, I’d love to see you, or, if you think your church might profit from a similar course, don’t hesitate to reach out!

Natural Law and Scriptural Authority course: There’s just two more weeks to sign up for my course this fall on how Protestants should think about natural law in relation to Scripture! Although designed as an introduction, the course features some deep dives into classic texts from the Christian tradition, as well as biblical exegesis and lots of class discussion. You can audit for just $225! Register here.

On the Bookshelf

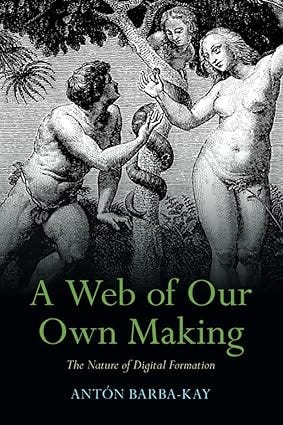

Anton Barba-Kay, A Web of Our Own Making: The Nature of Digital Formation (2023): After a third friend recommended this in as many months, I decided I needed to pick it up. And wow. Absolutely mesmerizing text, combining dizzying philosophical depth with hauntingly powerful prose. I have not read a book this slowly in years, so you’ll be seeing it here in this column for many weeks to come, as I slowly digest Barba-Kay’s extraordinary insights on the full meaning of the digital revolution. I’ll be reviewing this for American Affairs in due course.

Samuel Pufendorf, On the Nature and Qualification of Religion in Reference to Civil Society (1687): Pufendorf is often narrated as one of the “bad boys” of the Enlightenment, responsible for perverting the Protestant natural law tradition in a rationalistic and voluntarist direction, and for a Hobbesian demotion of religion to a department of the state. I was pleasantly surprised a few years ago to read his classic Of the Whole Duty of Man and the Citizen and to find it considerably more nuanced. And so I’m very excited now to dig into my second Pufendorf text, which I’ll be writing on for Ad Fontes/Commonwealth. This work is a key landmark in the development of Protestant theories of toleration and church/state relations.

Patrick Deneen, Regime Change (2023): Still chipping away at this and finding both plenty to profit from and plenty to disagree with. His discussion of the classical tradition of a “mixed constitution” was very helpful, although I raised an eyebrow or two at his passing remarks that the American Founders abandoned this tradition for a new liberal constitution. John Adams might have a thing or two to say about that.

Recommended Reads

I’ve avoided weighing in on controversies rocking the evangelical world the past few weeks following the publication of Meg Basham’s sensational Shepherds for Sale, which purports to offer a muck-racking exposé of progressive drift among evangelical leaders—driven in part, it would seem, by desire for financial gain. While I've no doubt this is a real problem, most of the discussion so far suggests that Basham has taken a 12-gauge shotgun to a problem that deserved a surgical scalpel, with little concern for collateral damage to faithful pastors laboring in difficult ministries. Many have felt compelled to publicly dispute the false or misleading portrayals of their past statements, and unfortunately these objections have generally been met with the kind of tribalistic “Narrative” thinking I discussed above. J.D. Greear’s lengthy apologia gives a good sense of the discourse, and I felt that this bracing read from Brian Mattson was also sadly on point.

“The Limits of Parents’ Rights” (Naomi Shaefer Riley, National Affairs): I was pleased to stumble across this piece last week, because it touches squarely on an issue that’s been bothering me for a few years. In the wake of CRT, transgender craziness, and endless mask mandates at schools, many conservatives mobilized in defense of “parental rights” to decide what goes on at public schools. Understandably in such cases, but by this logic, school phone bans are verboten as well. More generally, what if parents want to trans their kids or take them to drag shows? Are conservatives OK with that? Currently, our discourse is exceedingly muddled and opportunistic, and Riley’s essay is an important step toward wrestling through the underlying questions.

Get Involved

If you like this Substack, please spread the word with others. I’m just starting out, and steering clear of social media for now, and so would love to grow my subscribers through word of mouth! For now, this Substack will be totally free, but if you like the work I’m doing, please consider donating to it here by supporting EPPC and mentioning my name in the Comments.

If you have any questions or comments or pushback on anything you read here today (or recommendations for research leads I might want to chase down), please email me (w.b.littlejohn@gmail.com). I can’t promise I’ll have time to reply to every email, but even if you don’t hear back from me, I’m sure I’ll benefit from hearing your thoughts and disagreements.

https://cleartruthmedia.com/s/266/megan-basham-my-response-to-jd-greear

Brad, in your first sentence under What to Read, you say you’re not going to weigh in on Megan’s book at this time but you claim that she wrote this book for financial gain. Really? What would make you say such a thing? I hope you’ll answer this question tomotmorning at Holy Trinity. My next observation is that you refer to “discussions” about the book, implying that you’ve obviously not read the book. I hope you will read Megan’s book including her extensive notes at the end of each chapter. She has the receipts. The above discussion is worth watching too - my favorite of all the ones I’ve seen. I’ll also post her response to JD Greear.