On the first day of the Christmas holidays, I took my family to downtown DC, ending the day with what we had envisioned as an idyllic skate at the ice rink in the National Gallery’s Sculpture Garden. Although it was lovely, as ice skating always is, the experience was marred by the presence, for most of our one-hour skate, of a cluster of young women for whom the rink’s only value was as background scenery for Instagram glamour shots. Despite the freezing evening, they’d shown up in clubbing attire underneath their jackets, which they kept shedding in order to photograph one another in the most suggestive and meretricious poses they could muster.

Never mind that they couldn’t skate to save their lives or that the rest of us were trying to skate around them, and constantly forced to swerve to avoid them. Never mind that they had, fifteen minutes in, already managed to capture enough angles and poses to fill the most extravagant social media timeline. So enthralled were they by their own pantomime that they seemed oblivious to the ice, the skaters, the cold—to anything beyond their phones and how they imagined themselves appearing within those black mirrors. I was reminded of the line from Inception, “the dream has become their reality.”

More than that, I was reminded of what I had been reading and reflecting on in Anton Barba-Kay’s A Web of Our Own Making, of which I finally completed my massive review essay for American Affairs just after New Year’s. For Barba-Kay’s contention is that the greatest peril of digital formation is not that we will be completely sucked into a digital fantasy and abandon the flesh-and-blood world, like the dream-sharers of Inception, or the hikikomori of modern Japan, but rather that it will tempt us, while still inhabiting the real world, to try and remake it in the digital image, to try and force it into a digital mold. As I write in my review,

The digital mirror offers us the ultimate fulfillment of Narcissus’s delusion: to discover an image of ourselves that we can fall for. The digital mirror is always a deceptive one, though. While pretending to show us the world as it is, it offers us instead the world as we want it to be, or think we want it to be, and systematically blurs the line between image and reality. To filter the world without seeming to—that is the godlike power the digital holds out to us, and through which Instagram rakes in its billions. But the worst thing that can happen to us is not that we will be tricked by the image into believing it really is the real thing (we are not so foolish as Narcissus!) but that, wishing to make it real, we will, with increasing desperation, reconfigure our real world to make it conform to the digital, and forget how to live within it. “We warp what’s best in us to suit the medium precisely because it feels close enough. We leap to the conclusion, close the gap to make it so, so seeking our salvation in coveting what we must continually fail to possess” (245).

“We are looking to find ourselves and we are continually failing to, while all the while remaking ourselves for the purpose,” observes Barba-Kay (240). The greatest danger of the digital, he warns, is not that it will wholly replace the world of embodied experience—the wild dreams of transhumanists or VR goggle designers have, thus far, continued to break on the rocks of humanity’s stubborn attachment to physicality. The danger is that, while continuing to live in our bodies and their surroundings, we will continue to subconsciously remold them in imitation of our digital ideals-cum-idols.

The young women in the sculpture garden had come to see the ice rink not as a place within the physical world, but as a perfect canvas for their digital self-curation. They were warping what was best in themselves in order to suit the medium.

Of course, in the process, they were also warping it for everyone around them. And this is the second, perhaps more important, point that I wish to make about the nature of digital (de)formation, one that Barba-Kay addresses only fleetingly. It is the great seduction of digital technology to make us think that we are only ever making choices for ourselves. Wherever I am with my phone, I feel that I am alone with it, whatever else is going on around me. Every individual decision to pick it up and tune others out feels inconsequential; as Barba-Kay writes, “while no single thing we ever do online seems momentous, dire effects emerge from aggregates of our collective use.”

The collective action problems of digital media expose the lie in our modern individualism, as we experienced at the Sculpture Garden. There were probably at least 100 skaters on the ice, but the four aspiring models changed the experience for everyone. Not only did we all have to alter our skating patterns to avoid them, at the risk of causing secondary collisions, but more fundamentally, they altered the ambience of the whole space. Rather than feeling part of a genuinely public space, one felt at every moment that one was intruding on something private—or something that ought to be private. A space that one might have expected to be the most family-friendly venue in DC was transformed into a racy nightclub or boudoir. I felt bad for my sons. I too had to grow up in a world without much in the way of modesty standards, but I at least could choose whether or not to look; today, whether on the beach, at the park—or yes, even at the skating rink—one’s eye is likely to be arrested by the exhibitionism of clusters of young women swapping phones and posing for one another.

It is an interesting quality of digital media that even as it de-sexualizes by detaching us from our bodies it also encourages us to hyper-sexualize our behavior. Men are tempted to use the medium for exaggerated displays of machismo, braggadocio, and ritual combat; women for beauty pageants that sometimes leave little to the imagination. And of course, because we remain located in the offline world even as we let the online world set our expectations, these bad habits flow over to real life, deforming and degrading it.

There is also a contagion effect to such bad etiquette. As our skate went on, I noticed more and more people pausing on the ice to try and set up the perfect photo, making it increasingly perilous to circumnavigate the rink. It is a feature of our fallenness that we tend to gravitate toward the least common denominator, taking one person’s bad behavior as tacit permission to imitate it ourselves. We see this in more mundane settings every day—one person picks up their phone at a family gathering or church function, and soon all of us are staring down at our hands rather than engaging with one another. And of course, the worst thing about collective action problems is that even those who are most resolute in opposing the trend have no choice but to either join it or suffer its effects anyway: if I decide to stubbornly hold out as the one person in the room not bending over my phone, I’ll only have the pleasure of looking at the tops of everyone else’s heads.

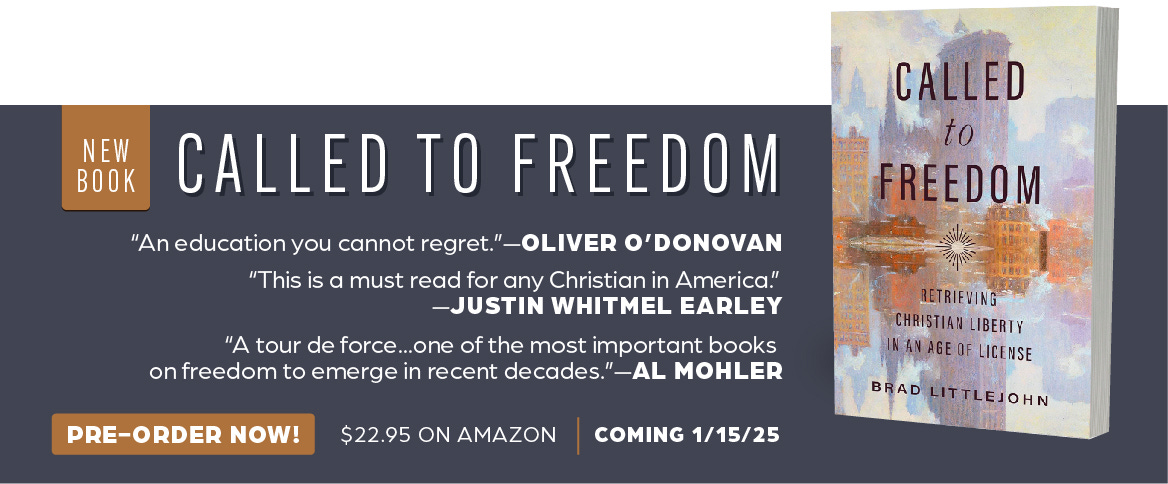

This is a clear example of a fundamental feature of freedom that I discuss in my new book: freedom is not merely—or perhaps even primarily—a quality of individuals but of communities. We deceive ourselves into thinking that each and every one of us can make our own choices about what to do online or offline, leaving everyone else equally free to make different choices. But obviously that is false. A social event where others have chosen to catch up on X rather than catch up with one another is a social event where I will no longer have the same freedoms as I otherwise would have. An ice skating rink which some have chosen to turn into an Instagram canvas is one where others will no longer be free simply to enjoy a skate.

To complain about any one of these situations can invite charges of curmudgeonliness, a “kids these days” griping that afflicts every generation in our fluid modernity. But of course, I am as guilty as anyone, albeit with a slightly different set of vices. The hyper-efficiency and hyper-connectivity of digital life tempts us to be always engaged, always available, always at work; something important is always happening elsewhere that seems to justify the fragmentation of my attention from the people and places right in front of me. I may not try to justify my existence by taking glamour shots (something for which the world is no doubt very grateful!), but I do by trying to look busy and productive, pretending to myself and others around me that the world cannot wait for me to read this one email or reply to this one text.

If Barba-Kay is right, we ignore these trends at our peril; we are rapidly becoming desensitized to the deformation of our common life and public space. Just as the most livable cities have carved out pedestrian-only spaces, so we must look for ways to carve out phone-free spaces, to resist the continued colonization of our lived environment with the rituals of digital performance.

On the Bookshelf

With huge writing commitments this month, I’m making indecently slow progress through several books listed below; will highlight just a couple for now.

Byung-Chul Han, Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power (2017): Wish I’d known about this one sooner. The first chapter is entitled “The Crisis of Freedom” and has some fascinating insights I wish I’d had the opportunity to incorporate into my book. Among them is a concept for which Han has become particularly known, that of “auto-exploitation” or “self-exploitation,” something perfectly exemplified in the phenomena described above:

“Today, we do not deem ourselves subjugated subjects, but rather projects: always refashioning and reinventing ourselves. A sense of freedom attends passing from the state of subject to that of project. All the same, this projection amounts to a form of compulsion and constraint—indeed, to a more efficient kind of subjectivation and subjugation. As a project deeming itself free of external and alien limitations, the I is now subjugating itself to internal limitations and self-constraints, which are taking the form of compulsive achievement and optimization.” (1)

A.G. Sertillanges, The Intellectual Life: Its Spirit, Conditions, Methods: So many wonderful passages in this, but perhaps the best are those where Sertillanges warns the intellectual not to think that he can simply retreat into his study, and not to be frustrated when called into the distractions of everyday life, but rather to look for the eternal in the temporal, the profound in the mundane:

“Learn to look; compare what is before you with your familiar or secret ideas. Do not see in a town merely houses, but human life and history. Let a gallery or a museum show you something more than a collection of objects, let it show you schools of art and of life, concepts of destiny and of nature, successive or varied tendencies of technique, of inspiration, of feeling. Let a workshop speak to you only of iron and wood, but of man’s estate, of work, of ancient and modern social economy, of class relationships. Let travel tell you of mankind; let scenery remind you of the great laws of the world; let the stars speak to you of measureless duration; let the pebbles on your path be to you the residue of the formation of the earth; let the sight of a family make you think of past generations; and let the least contact with your fellows throw light on the highest conception of man. If you cannot look thus, you will become, or be, a man of only commonplace mind. A thinker is like a filter, in which truths as they pass through leave their best substance behind.” (74)

David Innes, Christ and the Kingdoms of Men: Foundations of Political Life (2019): I’m reading this for a Regent course I’m teaching, and wow—how did I not know about this book? This is very very good, especially the treatment of the relationship of law to piety and morality. Definitely don’t agree with everything, and hope to share further thoughts here when I finish the book, but for now, I highly recommend this as a primer on Protestant political theology.

Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace

Larry Siedentop, Inventing the Individual: The Origins of Western Liberalism (2017)

Coming down the Pipe

Lots and lots things, but one especially:

Support my Work

Since writing is much of what I do for a living, and you, my readers, appreciate that writing, I’ve recently added a paid subscription tier for those who want to support my work with a small annual or monthly contribution. If you’d like to see more about how our technological culture is reshaping our understanding of what it means to be human, what we can do as citizens to fight back, and what we can do as Christians to chart a better path, consider a paid subscription. If you’d like to see more of what a classically Protestant understanding of authority, freedom, and law looks like in a (post-?)liberal society, consider a paid subscription. If you’d like access to the full archive of my posts (40 posts and growing), consider a paid subscription.

But I plan for most of my posts to continue to be available for free to all subscribers; so if you’re one of them, just help me out by spreading the word and encouraging others to subscribe, or by donating to EPPC and mentioning my name in the comments.