Sneak Preview: Called to Freedom

When it comes to freedom, American Christians inhabit two parallel worlds of discourse

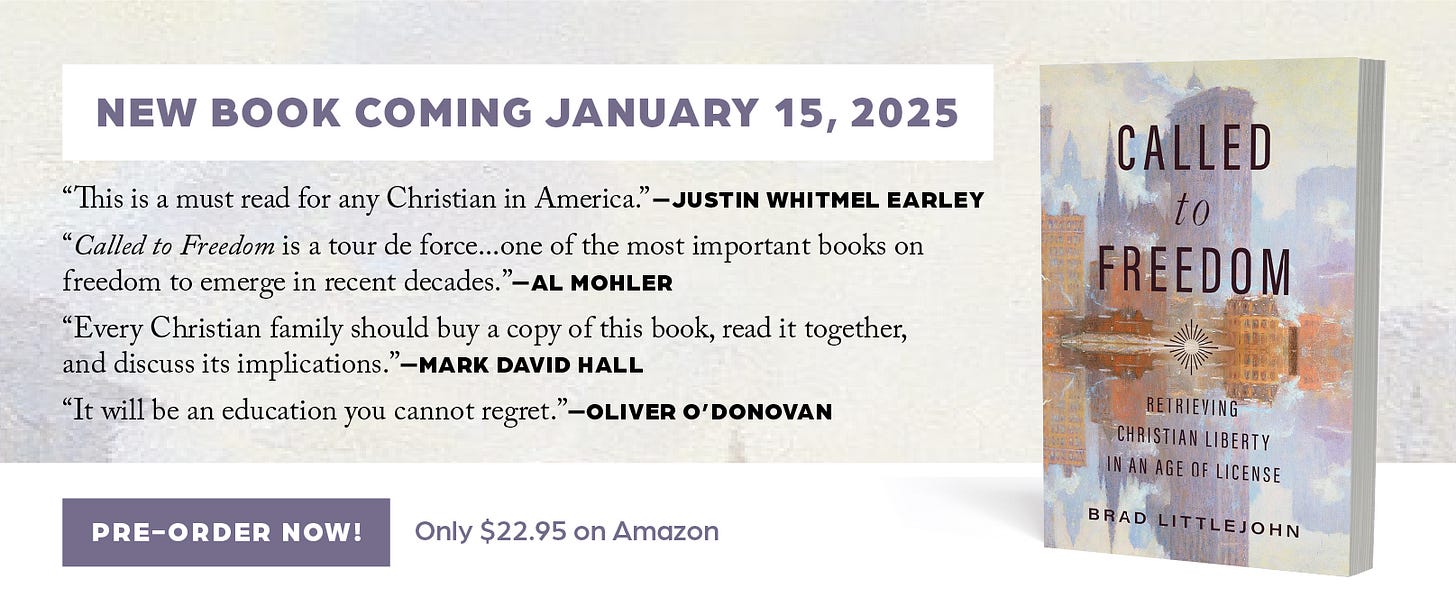

In less than two months, my newest book, Called to Freedom: Retrieving Christian Liberty in an Age of License, will be released. Although I’ve published a few books before, this is probably my most important to date. In it, I’ve sought to distill over a decade’s reflection, research, and writing at the intersection of theology and political philosophy into a concise, accessible guide to one of the central doctrines of the Protestant faith, so often misunderstood and misconstrued in our age of libertinism and libertarianism.

I begin by explaining the fundamental distinction between individual liberty and corporate or institutional liberty that I developed in my much longer and denser Peril and Promise of Christian Liberty (2017), along with the more familiar distinction between “negative liberty” and “positive liberty” used by many modern political philosophers. I also map a third distinction, critical to the Protestant Reformers as well as many classical philosophers, that of “inward liberty” and “outward liberty.” With this three-dimensional map of freedom in hand, I go on to expound the important differences between spiritual liberty, moral liberty, and political liberty, so often confused in our contemporary discourse. In the final three chapters, I apply these categories to three key case studies: (1) how does technology expand or destroy our freedom? (2) what does it mean to have a “free market”? (3) what is “religious liberty” and why should we protect it?

I’ll be featuring lots of interviews and talks related to the book starting in January, but I wanted to go ahead and tee up the release with a sneak preview, drawn from the book’s Conclusion. I hope your interest will be piqued and you’ll pre-order here. There’s also a chance to get an early copy and access to an exclusive webinar event if you want to join my launch team—just email me if interested!

When it comes to “freedom,” many American Christians inhabit two parallel worlds of discourse. At church, in Bible studies, and in their devotional life, they learn about how “true freedom is found in Christ”: how sin is the worst form of slavery and how Jesus sets them free from sin. Freedom is a feature of their inner lives, an experience of the mind or soul—and significantly, it involves committing to one path, only one Way. Yet the rest of the week, when watching the news, doing their shopping, or arguing on social media, “freedom” is found anywhere but in Christ. It is a political or economic or therapeutic slogan, a promise for liberation from the burdensome expectations or demands of other people, a promise fulfilled in fewer rules, more stuff, and more space to call their own. Freedom is a feature of their outer lives, something experienced within the world, and something that avoids commitment and demands the maximation of options and choices.

For many of us, I think, these two different ideas of freedom travel merrily along their parallel tracks without touching. We barely pause to think about how differently we use the word in different contexts, just as we do not think twice about referring to both insects and software glitches as “bugs.”

Many of us, though, make some attempt to bring the two discourses together, either adjusting our notions of spiritual freedom to conform to our worldly notions of political freedom or seeking to sacralize political freedom with spiritual significance. The former tendency appears in the rise of antinomianism among American Christians: the idea that to be “set free in Christ” is to be liberated from laws and moral expectations, that “Jesus loves us just the way we are” and we shouldn’t feel any pressure to change. It can be seen in an even more extreme form in the “prosperity gospel,” which encourages Christians to think of their spiritual liberation in Christ as a ticket to worldly freedom, understood in the crassest terms as the multiplication of their buying power.

The latter can be seen in the tendency of many American Christians to endow America itself with spiritual significance as the unique vehicle of God’s purposes in the world. From within this understanding, American ideals of political freedom come to be seen as something much greater and nobler than merely the improvement of democratic institutions—the Constitution becomes rather a kind of Fifth Gospel by which God announces his purposes to save the kingdoms of the world by bringing them under the sway of American liberty. Such idolatrous visions have been part of the American imagination almost since the beginning of our nation, and they have become only more dangerous as hope in America has dimmed. Fearful that the nation on which they have staked so much of their sense of purpose will fail to achieve its promise, some American Christians seem ready to stake everything on one last throw to try to “make America Christian again” by any means necessary.

We may be quick enough to see the errors in these conflations of sacred and secular visions of liberty, but these visions testify to our instinctive longing to reintegrate these two divided halves of our souls. Freedom is not merely a spiritual reality or a worldly ideal; it is not merely inward or outward. Freedom, rather, is experienced above all in the conformity of the soul to reality, the fit between our wills and our world, that moment when everything clicks into place and we find ourselves able to be and to do what it is we feel meant to be and to do. The freedom of the skilled violinist to express the melodies welling up within her on a perfectly tuned instrument, the freedom of the seasoned alpine skier with acres of white powder spread out below him, the freedom of a great orator with a life-or-death argument to make and an audience hanging on her every word—each of these describes an experience in which inner life and outer life have been brought into alignment, in which the soul itself has been finely tuned as an instrument to carry out a sense of vocation, and in which the world offers itself as a fit vehicle for those purposes because they conform to the norms God has built into creation.

As we have seen in this book, however, and as we experience every day of our lives, this ideal alignment of purposes with possibilities can be broken in any number of ways. We may find ourselves with a clear sense of purpose but frustrated by circumstances, like the budding young musician whose family cannot afford an instrument or lessons. Or we may find ourselves with the world at our feet but at the mercy of our desires—like a billionaire playboy who could have anything he wants but who cannot see beyond the next bottle of alcohol or the next sexual escapade.

Nor can we recover freedom simply by aligning inward desires with outward conditions. For our inner lives themselves are complex and conflicted. Our desires are at war with one another and at war with our Creator. “Unite my heart to fear your name” (Ps 86:11), prays the psalmist, recognizing that the greatest threat to piety is plurality—the inability to bring the conflicted fragments of his soul together in obedience to God. Behind and beyond all these warring desires lurk the shadowy fears of failure, inadequacy, and judgment, the worry that even if I could get my act together and accomplish something for once, someone would be standing over my shoulder saying, “Not good enough,” or that someone else would come along and reduce it to rubble. “It is an unhappy business that God has given to the children of man to be busy with. I have seen everything that is done under the sun, and behold, all is vanity and a striving after wind” (Eccl 1:13–14).

Freedom therefore must start at the innermost heart of our being, as we saw in chapter 2, as we hear the word of love and the promise that sets us free from fear, futility, and forgetfulness and that makes us, in the words of the Heidelberg Catechism, “wholeheartedly willing and ready from now on to live for him.”

Newly Published

“Pro-Family is the New Pro-Life” (WORLD Opinions): Last week I spotlighted Emma Green’s excellent new profile in The New Yorker of the pro-family movement on the New Right. In my latest column for WORLD Opinions, I summarize the key takeaways from her article, as well as highlighting two other areas where the new pro-family movement needs to pursue aggressive policy reform: education and technology. I conclude, “in the tumultuous new political landscape, pro-life conservatives will have to throw out the old playbook, but we can’t forfeit the game. The new GOP coalition is ripe for fresh thinking about the relationship of life, work, marriage, and family, and Christians must take the lead in forging a comprehensive pro-family agenda for the next four years and beyond.”

Coming down the Pipe

Amicus brief in Free Speech Coalition v. Paxton (co-authored with Clare Morell): This is off to the printers tomorrow after Herculean labors and more edits than I care to count. Part of a massive coalition effort to finally take Big Porn down a notch after nearly three decades of legal carte blanche, our brief demonstrates that the governing precedent in this field of law, Ashcroft v. ACLU (2004) is factually obsolete, premised as it is on the now-discredited claim that parental control filters can sufficiently protect children from obscene content online. “For too long,” we conclude, “our legal regime surrounding pornography has left parents to fight a one-sided war against Big Tech and Big Porn on their own, refusing to recognize the exploitative behavior of many of these industries, aimed at the most vulnerable members of society.” I believe a digital version of the brief will soon be available on the EPPC website, and we’ll also be writing a more popular version of some of the arguments for First Things. Stay tuned!

“Taking the Easy Way Out?” (WORLD Opinions): With the UK now seriously considering joining the ranks of developed nations that have legalized physician-assisted suicide, it’s time to take the growing support for euthanasia with deadly seriousness. As with most issues on which social conservatives keep losing, it cannot be treated in isolation from broader cultural and yes, technological (sorry to be a broken record!) trends. In a society in which technology has conditioned us to look for the easy way out of any uncomfortable situation, we simply no longer have the cultural resources that enable us to make sense of prolonged suffering, or to support others through it.

On the Bookshelf

What with the amicus effort consuming much of my bandwidth, I’m only actively reading two books right now:

Christine Rosen, The Extinction of Experience: Being Human in a Disembodied World (W.W. Norton, 2024): Finished this earlier this week. Lots of food for thought, though I must say that I think it is a good illustration of the maxim “Less is more.” Rather than digging deep into a few phenomena of our increasingly digitized, disembodied relation to the world and one another, she offers a shotgun-style smattering, skimming along from one baleful trend or unsettling observation to another, without pausing to really unpack and analyze any one in particular. This, to me at least, manages to give a very well-researched book an anecdotal, impressionistic flavor, which is probably not quite what our moment needs. That said, one cannot ask everyone to read Barba-Kay instead—A Web of Our Own Making is far too densely woven for most readers—and so many may find this an easier point of access to the conversation.

A.G. Sertillanges, The Intellectual Life: Its Spirit, Conditions, Methods: This classic, which comes highly recommended from some of my wisest friends, has been sitting on my to-read shelf for quite awhile, and I decided that with Thanksgiving break before me, now is a great time to finally pick it up. Personally, I have always striven with the tension between the vita activa and the vita contemplativa, swerving ever unsatisfied between the two, but the move to DC has certainly drawn me deeper into the webs of the vita activa, leaving sometimes too little time for real reflection. Hopefully Sertillanges will prove a timely antidote!

Recommended Reads

“It’s Not Political Idolatry. It’s Boredom” (Samuel James, Digital Liturgies): If you only read one article this week, read this one. Really important take from Sam James on the sources of our current discontent.

“The language of ‘political idolatry’ is nice because it frames the issue in either/or terms. Either you worship Christ, or you worship politics. And that’s true as far as it goes. But, if the line of thinking above is correct, most people don’t worship politics. Their relationship with politics is not worshipful, it’s neurotic. They are not gratefully receiving the promises of an idol, they are restlessly trying to create their own promises.

So my suggestion is that many cases that have been identified as political idolatry are actually cases of pathological boredom with everything that’s not politics. The best explanation for a neurotically restless relationship with political content is not positive (people worship politics), but negative: People disregard other things.

…

So maybe the way Christians talk about politics and American life could benefit from a realization that the real idolatry is one that is dug down deep into our lifestyles and sense of self. Instead of asking, “What do we love,” maybe we should ask, “What do we not love?” Remember that the Book of Common Prayer actually repents of sins of omission before sins of commission.

“When the Bough Breaks” (Oren Cass, Understanding America): Now that I’ve subscribed to Oren Cass’s Substack, I warn you that I may be posting links to it every week from here on out. This column was deeply moving, engaging as it did with a recent New York Times feature on “The Unspoken Grief of Never Becoming a Grandparent.” Cass deftly dissects the article as a reductio ad absurdum of our culture of self-gratification and childlessness, noting with astonishment just how much the Times seems to take it for granted that while we may express a certain sentimental sadness over a generation unwilling to take up the burdens of childrearing, we could not dare express anything approaching moral disapproval. Cass quotes from his First Things lecture earlier this year, which I had forgotten was so good: “We begin our lives with an incalculable debt. That we did not choose this debt is of no moral import—it is inherent to our existence. And we have only one way of repaying it: to work equally hard to bring about the next generation.”

“Ladies and Gentlemen, the Northeast is Burning” (John Vaillant, New York Times): I don’t talk about climate change often, but when I do … people have a way of getting ticked off. Seriously, though, the strangest thing about the climate change discussion is that those who say they don’t know why the world is warming tend to be blissfully unconcerned about the fact. This defies common sense—if your basement starts filling with water, you’ll be equally concerned whether it’s from a busted pipe (anthropogenic) or a rainstorm outside (natural causes); in fact, you might be more concerned in the latter case, because you’ll feel more powerless. And if you aren’t sure what the cause is yet, you’re generally more alarmed, because you don’t know yet what you should do.

So my modest proposal is this—let’s set aside for a moment debates about why exactly the weather is getting so weird, and at least face up to the fact of climatic changes as an urgent public policy priority. There’s nothing to be gained for anyone in pretending there’s nothing to worry about.

Help Me Do More

It’s that time of year again—when families gather around laden tables with steaming aromas, when the holiday music starts blaring through every speaker, and when anyone and everyone with any affiliation to a non-profit starts asking for money.

In all seriousness, though, everything I do here at EPPC is donor-supported, as is the work of our few dozen scholars, who continue to have an impact on renewing culture and shaping public policy far out of proportion to the size of our institution. If you’ve appreciated what you’ve seen from me on this Substack and elsewhere this year, I’d like to invite and encourage you to consider supporting my work going forward, so I can continue to build my scholarship, writing, and policy work, as well as developing programs to magnify these efforts. If you’d like to talk more about financial support, just shoot me an email (w.b.littlejohn@gmail.com), or if you’d like to go ahead and make a gift, click the button below and put my name in the Comments field!