The Boethius Option

A vision for the scholar-statesman in the Age of Trump

“It is always dangerous to draw too precise parallels between one historical period and another; and among the most misleading of such parallels are those which have been drawn between our own age in Europe and North America and the epoch in which the Roman empire declined into the Dark Ages. Nonetheless certain parallels there are. A crucial turning point in that earlier history occurred when men and women of good will turned aside from the task of shoring up the Roman imperium and ceased to identify the continuation of civility and moral community with the maintenance of that imperium. What they set themselves to achieve instead—often not recognizing fully what they were doing—was the construction of new forms of community within which the moral life could be sustained so that both morality and civility might survive the coming ages of barbarism and darkness. If my account of our moral condition is correct, we ought also to conclude that for some time now we too have reached that turning point. What matters at this stage is the construction of local forms of community within which civility and the intellectual and moral life can be sustained through the new dark ages which are already upon us. And if the tradition of the virtues was able to survive the horrors of the last dark ages, we are not entirely without grounds for hope. This time however the barbarians are not waiting beyond the frontiers; they have already been governing us for quite some time. And it is our lack of consciousness of this that constitutes part of our predicament. We are waiting not for a Godot, but for another—doubtless very different—St. Benedict.”

So ends Alasdair MacIntyre’s 1981 book After Virtue, a book (and a concluding passage) that has haunted conservative thought over the four decades since, though its message has become somewhat distorted in transmission. One culprit is Rod Dreher’s 2017 bestseller, The Benedict Option, whose jacket description proclaims, “Today, a new post-Christian barbarism reigns. Many believers are blind to it, and their churches are too weak to resist. Politics offers little help in this spiritual crisis. What is needed is the Benedict Option, a strategy that draws on the authority of Scripture and the wisdom of the ancient church. The goal: to embrace exile from the mainstream culture and construct a resilient counterculture.” In his new book Cultural Sanctification: Engaging the World Like the Early Church, Stephen Presley invokes Benedict in the context of how Christians can successfully engage the culture given “the death of Christendom and the loss of cultural power.”

Notice the shifting trajectory here: while MacIntyre lamented the rise of “barbarism,” Dreher interpreted that as “post-Christian barbarism,” which Presley then rendered as “the death of Christendom.”

In recent years, such concerns have blended with formulations such as Aaron Renn’s “Negative World” to turn much of the conversation in Christian circles to: “how can we equip our people to survive and thrive in an increasingly anti-Christian world?” This is an important conversation to have, for sure. And yet it is not the only conversation we need to have, or the one that MacIntyre’s metaphor points us to.

St. Benedict, after all, did not live during a period of de-Christianization. Quite the contrary. The Mediterranean world had become officially Christian less than two centuries before and the Church was continuing to grow in importance and influence. The barbarian tribes that flowed to and fro throughout the crumbling shell of the Roman Empire in the 5th and 6th centuries were, for the most part, already converted to Christianity (albeit in some cases an aberrant Arian form of it). No, the problem that Benedict faced was an age of barbarism, a breakdown of civilization. That is also, I would argue, the great problem that we face.

So what do we mean by barbarism?

In its original Greek usage, “barbarians” were those who did not speak Greek and did not share Greek customs. Since Greek remained the language of learning and of high culture throughout the long period of the Roman Empire, the loss of the Greek language in the West during the barbarian invasions represented a profound step backward for civilization. Barbarism, then, is a loss of high culture—of the texts and forms of speech and formation of virtue that is possible only within a society that enjoys relative peace and stability, the rule of law, and, as MacIntyre says, a commitment to the “maintenance of civility and moral community.” A high culture requires the formation and perpetuation of an elite that understands itself to exist not for its own interests alone, but for the larger moral community of which it is a part, and of a broader society that, if not always understanding or imitating this elite, at least grudgingly follows the lead they set and imbibes some of their cultural productions secondhand.

From this standpoint, it seems clear that our own culture is well on its way to a descent into barbarism. The main culprit is not the “barbarian invasions” of immigrants who do not speak our language or know our customs, although that may well be accelerating our decline. As with Rome, decay from within preceded decay from without. A shared sense of moral community has given way to a clamor of fractious tribes who must settle their differences through violence (thus far in our case, simulated, rhetorical, and digitized violence, but it may not remain there). A self-replicating caste of elites has turned inward and ceased to understand their central role in society as one of transmitting a common language, with a canon of great texts and the means of understand and apply them. The culture at large has become an anti-culture, half of whom didn’t read a single book last year—even the trashiest romance novel.

All this is as true within the church as without. In Benedict’s day, plenty of people were still Christians, but they could no longer read nor write; they lacked the tools to weave the threads of their faith into the tapestry of culture or of law. Similarly today, many Christians are functionally illiterate. They do not understand their faith, its history, or its creeds. While they may cling to it with admirable simple piety, they have no conceptual framework for why it is rational, or how it has been and ought to be embedded in their culture’s political institutions, literary traditions, or norms of virtue.

Within such a society, we do need St. Benedicts who will rebuild intentional communities of moral formation and shared life outside the decaying cities, communities in which the wisdom of the past can be preserved and transmitted. Although we pooh-pooh “rote learning” and “vain repetition,” this is a lot of what Benedict’s monasteries did, faithfully copying texts they themselves barely understood, sometimes for centuries on end, until conditions were ripe again for a new flowering of learning and culture. But we also need St. Boethiuses.

Who was Boethius? His neglect in contemporary discourse is a scandal—itself an index of how far we have descended into scandal. He was born Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius in Rome in 480 AD, four years after the supposed “Fall of Rome”—when Odoacer, the Gothic general, took the throne from the head of his putative master, the last pale shadow of a Roman emperor, Augustulus Romulus. Of course, no one at the time saw it quite this clearly. Odoacer still nominally acknowledged the authority of the Emperor in Constantinople and the Senate continued to meet. Boethius himself would become a senator by age 25 and a consul at 30. But it was clearly a time of barbarism.

When Theodoric the Ostrogoth entered Italy with his forces in 489, a four-year contest between him and Odoacer was ended by a treaty of friendship in 493, in which both men promised to share the rule of Italy. Odoacer held a great feast in Ravenna and invited Theodoric to celebrate the treaty. After much drinking and merrymaking, Theodoric proposed a toast to Odoacer, drained his goblet, pulled out his sword, and literally clove Odoacer in two on the spot. Thenceforward he took the title “King of Italy” and consolidated his dominion over the peninsula for the next 33 years, succeeding so well that he is known to historians as Theodoric the Great.

It was this man, with his rough justice and uncouth manners, whose service Boethius would enter in his public career. Showing extraordinary skill as an administrator and leader of men, he made himself indispensable to Theodoric and in 522 was appointed magister officiorum, effectively Theodoric’s prime minister or “grand vizier.” He used his position to fight corruption and seek to restore some greater semblance of the rule of law as Rome had once known it.

However, this was not his primary claim to fame. That lay in his extraordinary learning. Educated from a young age in the Greek classics, Boethius came to manhood to find himself almost entirely alone in his knowledge even of the Greek language, much less the rich philosophical tradition that had developed within it and that had been a crucial matrix for the formation of Christian theology. The barbarism of his age was so complete that Greek, once the first language of all the educated classes, was essentially extinct west of the Adriatic. Boethius recognized that it was hopeless to try and re-educate everyone in Greek, and so, if learning, high culture, and the love of wisdom were to endure, he would have to translate.

“I shall translate into Latin every work of Aristotle’s that comes into my hands, and I shall write commentaries on all of them; any subtlety of logic, any depth of moral insight, any perception of scientific truth that Aristotle has set down, I shall arrange, translate, and illuminate by the light of a commentary,” he declared. He made impressive progress: Aristotle’s Categories, On Interpretation, Prior Analytics, and Sophistical Refutations, along with Porphyry’s logic textbook Isagoge, all received translations and commentaries. The commentaries were as crucial as the translations, for Boethius recognized that in an age of barbarism, you couldn’t just give people texts—you had to teach them again how to learn. Accordingly, he also wrote his own treatises on logic and theology as guides or entry points to the great tradition.

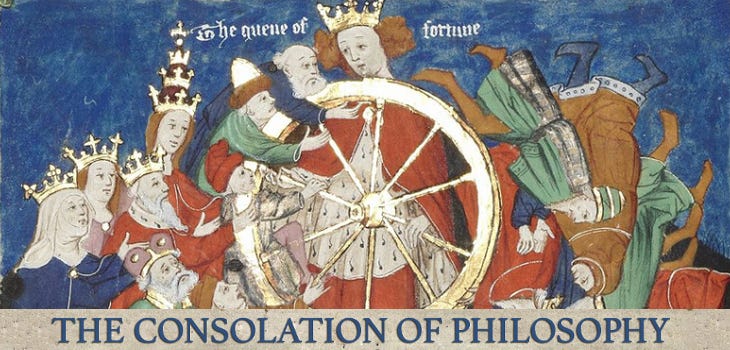

But he did not get that far. The vocation of the scholar-statesman, the lover of wisdom in a barbarian court, is a fraught one. It didn’t take long before Theodoric tired of having a magister officiorum who was so zealous about rooting out corruption, and Boethius was imprisoned, without access to his books, in 423. Facing a likely death sentence, Boethius realized that time was running out for his mission of passing the torch of knowledge on to succeeding generations. So he came up with a Plan B, one of the great masterpieces of classical culture. Writing from memory, he composed a dialogue about his predicament, The Consolation of Philosophy, which represented essentially a concise compendium of the accumulated wisdom of the ancient world—Platonic, Aristotelian, and Stoic—filtered through the lens of Boethius’s Christian faith. Through it the basic concepts and categories of classical civilization were preserved, in vivid and poetic form, for transmission to the Dark Ages to come.

The book succeeded beyond its wildest dreams. C.S. Lewis calls it “for centuries one of the most influential books ever written in Latin” and says “to acquire a taste for it is almost to become naturalized in the Middle Ages”—throughout which it was one of the most frequently-cited texts. But Boethius’s translations and treatises didn’t do bad either—for centuries, until Arab texts filtered west in the 12th century, they were essentially the Latin West’s sole source for Aristotle’s thought, and provided the matrix of scholastic logic for the discipline of theology. While Benedict’s monks were busily copying away in their candlelit monasteries, odds are it was Boethius’s texts they were copying.

But Benedict was dependent on Boethius in another way. Although Italy was a dark and lawless place during his life, it was not nearly so dark and lawless as it might have been. The relative peace and stability that the Ostrogothic Kingdom maintained, and which allowed Benedict to plant his monastery, owed no little debt to Boethius’s labors as a statesman, through which he managed to preserve a modicum of Roman law and order in a barbaric age. Of course, it did not end well for him—he was tortured to death in 524. But his sacrifice helped in the end to save and renew Christian civilization: both through his statesmen’s labors of holding chaos at bay a little longer, and through his scholar’s labors of planting seeds of renewal that would bear fruit in due time.

Today, I believe, at least some Christians are called not to be Benedicts, but Boethiuses. We need scholar-statesmen who will serve at the court of our Theodoric (Trump has not yet cloven his rivals in two with a sword, though he has certainly done the Twitter equivalents) and who will risk their own careers (although thankfully not yet their lives) fight to maintain a modicum of law and order in a world that is descending into tribal chaos. They will need all the skills of administration and statesmanship that classical education and the school of hard knocks can provide them.

At the same time, though, we must engage in the tireless work of translation. Our elite is gone or decadent, our people and our churches are illiterate, the great heritage of Western theology, philosophy, literature, and politics is largely out of reach for us. It needs to be translated and commented upon, put into a form that is accessible to an age of barbarism. Armed with such texts, our own new Benedictine communities—the classical Christian schools above all—can copy these texts and learn their truths by heart, passing down the torch of wisdom to a new generation until, in God’s good time, it is ready to again light up the world.

Beautiful essay. Thank you.

Excellent essay!