In The Abolition of Man, C.S. Lewis, like any good Irish-born Englishmen, tells a memorable little joke about the Irish : “It is like the famous Irishman who found that a certain kind of stove reduced his fuel bill by half and thence concluded that two stoves of the same kind would enable him to warm his house with no fuel at all.” Lewis applies the principle to the onward advance of technology, which in its quest to conquer nature by treating all things as mere matter and energy finally turns its efforts on humanity itself:

“The wresting of powers from Nature is also the surrendering of things to Nature. As long as this process stops short of the final stage we may well hold that the gain outweighs the loss. But as soon as we take the final step of reducing our own species to the level of mere Nature, the whole process is stultified, for this time the being who stood to gain and the being who has been sacrificed are one and the same” (71).

And indeed, this is an indispensable framework to think about technology, which so frequently seduces us with the idea that if two or three steps towards a cliff edge improves our view, two or three more steps will be even better. The development of a new tool for a time improves the capacities of the craftsman, but then beyond that point, may put him out of a job and lead to the disappearance of the craft altogether. Facebook might begin by improving and leveraging your network of real friendships, but beyond a certain point, crowds them out and leaves us all “alone together.” Joshua Mitchell has articulated a very similar point in his brilliant 2018 essay, “When Supplements Become Substitutes: A Theory of Nearly Everything,” to which the subtitle of this post was a shoutout.

And yet I am not here today to talk about technology, even if I have often used the “Irishman’s Two Stoves” analogy in that context. For it really is a theory of nearly everything. Consider the topic of religious pluralism.

I found myself considering that topic on Tuesday night as I sat in the audience of an EPPC “Crossroads of Conservatism” debate featuring Rusty Reno and Avik Roy, debating the proposition: “Resolved: Religious Diversity Has Weakened America.” (You can watch the whole video here.) It was a great conversation, a classic Prov. 18:17 debate where Rusty seemed to be winning the debate running away after his opening statement and then Avik seemed to have him on the ropes after his. Both gentlemen (both devout Christians, mind you) mounted sound and eloquent arguments in favor of, respectively, the importance of a Christian religious consensus (Reno) and of robust religious pluralism (Roy) to American public life.

And yet, as the debate went on, it became increasingly frustrating, for it quickly became clear that neither man was an absolute purist for their position; both, being intelligent and experienced men of affairs, tacitly recognized the truth of George Will’s great dictum: “the most important four words in politics are ‘up to a point.’” Reno certainly did not believe that America would be the strongest, best version of itself if populated 100% with conservative Christians—certainly not of the same denomination. He freely granted, not only that the coexistence of Protestants and Catholics within the same polity was a healthy thing, not only that the Jewish element in American society and public life had been a source of strength and enrichment, but even that a relatively small minority of other faiths posed no real threat to American institutions and could even contribute to American greatness. His point seemed to be simply that a successful society and a robust culture depend upon having a strong core of religious consensus, which in our case should be a Christian one.

Roy, for his part, did not seem to really think that America would be the strongest, best version of itself if it cultivated the maximum possible religious diversity (i.e., imagine a society made up of 100 very different religious sects each comprising 1% of the population). Indeed, he admitted that there were some religious groups that are in fact antithetical to American ideals and whose adherents would not make good citizens (e.g., radical forms of Islam). His argument made much of the historical examples of various minority religious groups thriving in America and helping America thrive (e.g., Jewish immigrants during and after World War II). But of course, these groups were and even now remain very small minorities within a dominantly Christian culture (quickly becoming a secular culture haunted by the ghost of Christianity).

I thus submitted the question, “Is it possible that both speakers ultimately agree that some religious diversity is good, but that there is a point of diminishing returns where there is too much diversity? If so, the debate would just be over where the ideal balance of homogeneity and diversity is.” Unfortunately the moderator never asked this question, so I am not sure how they would have answered it. But it seems obvious to me, at any rate, that with religious diversity as with many other forms of diversity, we are dealing with an “Irishman’s Two Stoves” problem. From a Christian standpoint, indeed, it might at first seem that the truly ideal polity would be one that was 100% Christian. But we know that this side of the eschaton, even the church itself will be full of tares, so a “100% Christian” society would be only nominally so, and experience shows that without some outside challenges, without some religious competition, to keep Christians on their toes, the quality and sincerity of Christian faith and practice would decline. This, of course, was Adam Smith’s famous argument for the good of religious competition in The Wealth of Nations—a monopoly religious establishment could get fat, lazy, and complacent, with little impetus to keep spreading the gospel or generating religious zeal. A competitive religious environment, however, would lead to healthy, vigorous churches. Nineteenth century America certainly seemed to bear out this hypothesis.

But Smith presupposed that the diversity he recommended would take place within a Christian-dominated polity. Indeed, he mainly had in mind the diversity of Protestant denominations. The American Founders broadened this, throwing the doors open to Catholics and Jews, and writing into the Constitution religious liberty for all, but again, with the assumption that other religions would likely be no more than a little extra spice in an overwhelmingly Christian (and indeed overwhelmingly Protestant) soup. Some might say this is inconsistent: “if some diversity is good, why isn’t more better?” But we know that’s not how the world works. A good educational institution, for instance, will thrive if (a) it has a clear majority consensus around a shared vision, (b) some variations within that majority about exactly how they interpret and apply that vision, and (c) a couple of eccentric dissidents on the margins who spice things up and keep the other faculty on their toes. It will not thrive if it cultivates either suffocating unanimity or such a radical diversity of viewpoints that no common culture is possible.

This point about religious liberty could be broadened to include many other liberties that once helped nurture our civilization but today, applied in excess, are poisoning it. Freedom of speech, for instance: a conversation is enriched, stimulated, and taken to a higher level if you open it up to allow everyone with relevant wisdom and insight to participate; it quickly devolves into futility if opened up to anyone and everyone. Indeed, the possibility for conversation of any kind disappears if all barriers to speech are removed, and you are left with a cacophonous shouting match; once that takes place, those actually interested in conversation will depart and re-convene behind closed doors. Within the arts, a few daring rebels against the conventional canons of excellence will help spur artistic progress, but the abolition of all canons in favor of a perpetual rebellion of all against all will destroy the art altogether.

Examples could be multiplied indefinitely, from the worlds of business, politics, or everyday life; indeed, the principle, when you stop to think about it, can seem so obvious as to be a banality. And yet it is startling just how consistently it is ignored in moral and political debates. A pastor or (particularly daring) politician says that we need more married people raising children, and the retort comes fast and furious, “So you think single people are second-class citizens?” Or consider the debate over immigration, where anyone who dares point out the blessings of immigrants is accused of wanting to overrun the country with them, and anyone suggesting we should have less is accused of wanting to ban and deport them all.

So next time you hear someone committing this fallacy, remind them of the Irishman’s two stoves. If they are not actually prepared to argue that something is a categorical good or evil, insist that they explain why want to see more of it or less of it, and then see whether (and where) their opponent actually disagrees. Anything else is just intellectual laziness.

Newly Published

“Something Wicked This Way Comes” (WORLD Opinions): “When I said Wicked, I didn’t mean that wicked!” Such is the gist of a lawsuit, Ricketson v. Mattel, filed by a South Carolina mother whose young daughter decided to check out the website mistakenly provided on the box of a singing Wicked doll. Let’s just say it went to some very wicked movies, but not to the Wicked movie. Accidental typo or not, it’s egregious enough that Mattel probably deserves to find itself on the end of a class-action lawsuit. That said, there’s something strange about the fact that Apple isn’t, when it sold the mother a device that came pre-loaded with easy access to this website and countless others more appalling. Thankfully, new legislation may finally be bringing accountability to app stores, as I note at the end of my column.

Coming down the Pipe

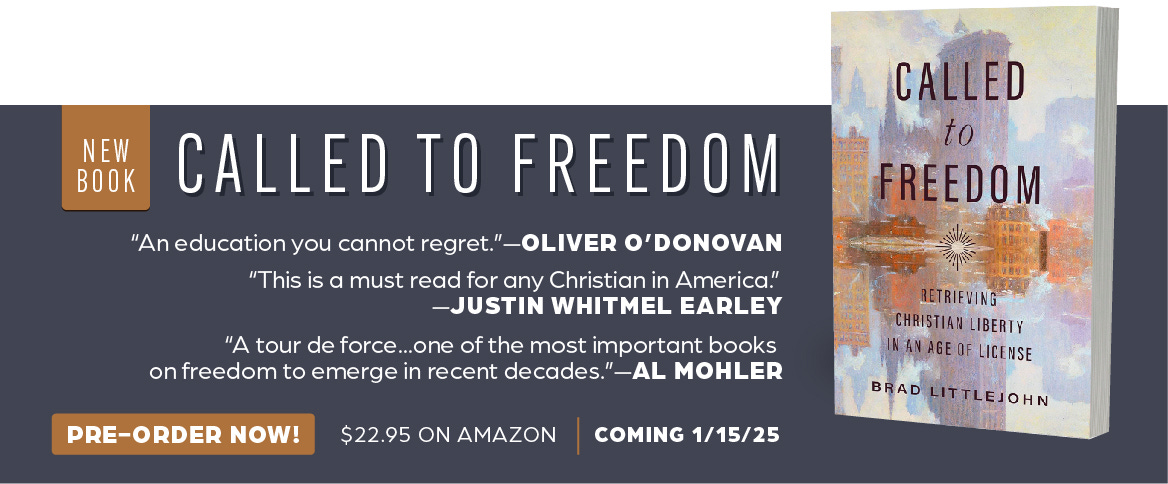

“For Freedom Christ Has Set Us Free” (The Gospel Coalition): This essay, summarizing many of the key themes of my forthcoming book, Called to Freedom, will publish next month at TGC. In it I lay out the basic threefold distinction that I work through in the book—spiritual, moral, and political liberty—and how each of the three relates to the others: moral and political liberty, rightly understood, will both depend on and shape one another, and both can only be durably possessed by a spiritually free people.

Podcast Appearances: This week, I sat down for interviews with three podcasts, The London Lyceum, That’ll Preach, and Kingdom and Culture, with episodes for each set to release around the middle of January. All three podcasts were interviews about Called to Freedom, but each of them went in different directions highlighting different themes, and they were all fun conversations where I enjoyed fleshing out key ideas. The last one, from Kingdom and Culture, even included a bonus extra interview episode on AI and my forthcoming essay, “Stop Hacking the Human Person.” I’ll of course link all of these when they publish in January.

On the Bookshelf

Byung-Chul Han, The Disappearance of Ritual: A Topology of the Present (2020): In my endeavor to self-educate on the discourse around technology, I’ve been encouraged to read Byung-Chul Han. But which Byung-Chul Han book? That was not so clearly communicated, and it turns out he writes loads of short little books. Not knowing where to start, I tried this one. I’m not a huge fan of the style—lots of concise, punchy but elusive, incompletely fleshed-out assertions—and there’s some bizarro bits in the second half. But lots of rich and thought-provoking ideas. This passage captures a lot of key claims from the book:

“Today, we are constantly and compulsively playing to the gallery. This is especially the case, for instance, on social media: the social is coming to be completely subordinated to self-production. Everyone is producing him- or herself in order to garner more attention. The compulsion of self-production leads to a crisis of community. The so-called ‘community’ that is today invoked everywhere is an atrophied community, perhaps even a kind of commodification and consumerized community. It lacks the symbolic power to bind people together” (13).

I’m finishing it today and will move on to his Psychopolitics (2017).

Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace: I really am terrible about making time for leisure reading of late, but am making progress through this masterpiece again. I was motivated to read it earlier this year after watching the 2016 War and Peace miniseries directed by Tom Harper (available free on Prime if you’re a subscriber); I can recall few cinematic experiences that have more impressed or moved me, and I was curious whether it was just a good film series inspired by a book, or whether it was actually a good adaptation of the book. As I read through the novel, I continue to be impressed at each turn by how well and how accurately key scenes and characters were rendered in Harper’s adaptation. I suppose I can’t truly recommend it until I’ve finished the book—perhaps there are some egregious departures from the book in the latter part. But thus far, two thumbs up on both book and film.

Larry Siedentop, Inventing the Individual: The Origins of Western Liberalism (2017): This book comes highly recommended, often mentioned in the same breath as Tom Holland’s Dominion: “Christianity gave us most of what you love/hate about the modern world, so deal with it.” Will be reading this over the Christmas holiday.

William Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1961): Making slow but fascinating progress.

A.G. Sertillanges, The Intellectual Life: Its Spirit, Conditions, Methods: Put this on pause during some intensive writing this month but look forward to finishing over Christmas.

Recommended Reads

“Modernity’s Self-Destruct Button” (Louise Perry, First Things): This essay has been creating a bit of buzz, and rightly so. I have often wondered why the looming dystopia of low birth rates has not dominated cultural and political discourse more for the past ten years. In this essay, Louise Perry faces squarely up to the catastrophe before us, and suggests that the end result may well be a rollback of many of the luxuries of modernity (which we have come to think of as necessities) that were the product of a high-population growth society. “Modernity may be inherently self-limiting, not because of its destructive effects on the natural world, but because it eventually trips a self-destruct trigger. If modern people will not reproduce themselves, then modernity cannot last. One way or another, we’re going to return to a much older way of living.” This is absolutely essential reading.

“Smash the Technopoly!” (Nicholas Smyth, After Babel): I’ve been mentioning Neil Postman’s Technopoly in my last couple of Substacks, and if you don’t have time to read it and would like a quick intro to its key arguments, you couldn’t do much better than read this recent guest post on Jonathan Haidt’s Substack. “Postman distinguishes between a tool-using culture and a technopoly. All cultures have tools, but some cultures have moral resources necessary to constrain and direct the uses to which tools are put.” The greatest pathology of our modern condition is our unwillingness or inability to even ask questions about the pros and cons of a new technology before simply rolling it out to society at large, our determination to “move fast and break things.” Smyth thus points out that even if it somehow turned out that every empirical claim in Haidt’s The Anxious Generation were refuted, his most fundamental objection would still stand: we didn’t even ask these questions or consider these harms before running this social experiment.

“Pornography’s Big Lie: The Fear of Missing Out” (Mark Sanders): Given that on January 15th, I’ve got a book on freedom coming out and a SCOTUS case on pornography to attend, I’ve been thinking a lot about the connection between the two—indeed, already in the book, I use pornography as a classic example of Plato’s maxim, “extreme freedom leads to extreme slavery.” So I was intrigued to see this guest post on Anthony Bradley’s Substack come across my feed. This is a good pastoral resource to share with anyone you know struggling with pornography, and I particularly appreciated his observation that “the hunt as more intoxicating than the kill.” As I’ve written before, online pornography should be understood as more nearly an expression of the vice of “curiosity” than of lust strictly speaking. It is a specification of the much more general online phenomenon of restlessly seeking for the newest and latest information, only supercharged by the addition of sexual desire.

Help Me Do More

It’s that time of year again—when families gather around laden tables with steaming aromas, when the holiday music starts blaring through every speaker, and when anyone and everyone with any affiliation to a non-profit starts asking for money.

In all seriousness, though, everything I do here at EPPC is donor-supported, as is the work of our few dozen scholars, who continue to have an impact on renewing culture and shaping public policy far out of proportion to the size of our institution. If you’ve appreciated what you’ve seen from me on this Substack and elsewhere this year, I’d like to invite and encourage you to consider supporting my work going forward, so I can continue to build my scholarship, writing, and policy work, as well as developing programs to magnify these efforts. If you’d like to talk more about financial support, just shoot me an email (w.b.littlejohn@gmail.com), or if you’d like to go ahead and make a gift, click the button below and put my name in the Comments field!

When you're done with War and Peace you should try George Eliot. She's the closest thing to Tolstoy we have in English