What is a Free Market Anyway?

In economics as elsewhere, freedom is easier in theory than in practice

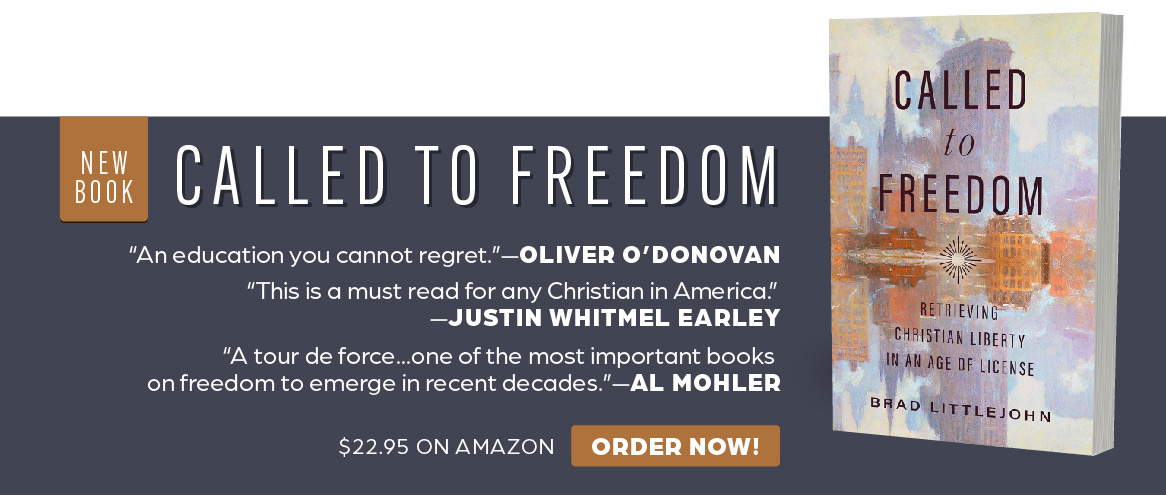

During the many podcast interviews I’ve done the past few weeks about my book, Called to Freedom, I’ve frequently been asked: “What first got you thinking about this topic?” My earliest memory of wrestling with the concept of freedom dates back to 2007, when I read William T. Cavanaugh’s little book, Being Consumed: Economics and Christian Desire. I remember very few details of the book, and indeed, for some reason didn’t even revisit it in the course of writing Called to Freedom, but it did first draw my attention to a fundamental tension within the conservative Christian worldview in which I’d been brought up: in what sense is the “free market” really free?

I particularly recall two holes that Cavanaugh punctured in the naïve celebration of free market capitalism that I’d often heard: first, he argued that the freedom of consumers was often maximized only at the expense of the freedom of laborers; second, that the freedom of consumers was often maximized only at the expense of…well, the real freedom of consumers themselves. On reflection, both insights seemed undeniable as a description of how real-world economies operate, but I wasn’t ready to simply throw in the towel on capitalism and embrace the faddish “Occupy Wall Street” socialism that was so popular among those of my generation from 2008 to 2012. Instead, the questions that Cavanaugh provoked sent me on a journey of wrestling with economics, theological ethics, and political theory that continues to the present.

Yesterday, in Comment magazine, I published an essay, “In Search of a Free Market,” adapted from my new book, Called to Freedom. In the essay, I focus chiefly on the second concern—how consumerism can tend to enslave its own supposed beneficiaries—but before I come to that, let me elaborate briefly on the first critique: the potential to exploit workers.

This, of course, is a common critique of the market economy going back to Marx and beyond, and it enjoyed a new heyday in the early 2000s as critics of globalization like Naomi Klein drew attention to the egregious working conditions of Asian or Central American “sweatshops”: our freedom to indulge in shopping sprees at Banana Republic, it turned out, was purchased at the cost of the blood, sweat, and tears of the people who actually lived in that banana republic. Of course, my free marketeer friends were ready with a response: the sweatshops were actually a blessing to the people who worked 80 hours a week in them. If they didn’t have those wonderful sweatshop jobs, they’d be working 100 hours a week in the rice paddies for even worse wages—otherwise, why would they have signed up for the sweatshop jobs at all?

This was, of course, a vastly oversimplistic response, although not without a nugget of truth in many cases. It really was true that jobs that might seem to us tantamount to slavery were often a ticket up the economic ladder for workers in developing economies in the midst of the growing pains of industrialization. That said, it seemed disingenuous to pretend, as so many right-wing commentators did, that all such market exchanges were free, uncoerced, and therefore beneficial to both parties. Such theory depended upon a strangely blinkered conception of “coercion,” one in which the threat of starvation somehow didn’t register as a constraint on a breadwinner’s freedom. The reality is that a worker who has no choice whether to take the terms of employment offered is not engaging in a free exchange, nor does he necessarily come out of the exchange better off; he may, in fact, be even weaker and more dependent as a result of it.

The standard “everybody wins” free-market theory, I later learned, applies only in hypothetical conditions where both buyers and sellers can easily choose to bargain with other contractual partners if they don’t like the deal on offer, and have equal negotiating power. In real life, people rarely have equal negotiating power. Of course, often the inequality is too small to matter that much, and the market approximates the model of free exchange. Sometimes, though, if there are few enough plausible sellers, a market is crippled by monopoly power. Or, if there are few enough viable buyers you have what is called monopsony power—this includes buyers of labor, or employers, who thus sometimes enjoy a distinct edge over workers. (I discussed this principle in an interview with Oren Cass a few years ago, and analyzed Sohrab Ahmari’s larger argument on this point in a review essay of his Tyranny, Inc.)

In other words, it’s silly to isolate economics from the social and political structures in which it is always embedded, and these structures always involve power dynamics. Through such power dynamics, market actors can and do seek to maximize their freedom at the expense of the freedom and flourishing of others. It is thus the essential task of good public policy to mitigate these imbalances and create the conditions where more genuinely free market exchanges can happen.

Still, there is another deeper problem that Cavanaugh identified, and it is this that I explore in my Comment essay: we can quite readily serve as the agents of our own unfreedom—an unfreedom others are only too happy to profit from, I should add.

From a classical and Christian standpoint, freedom is found in governing our desires, rather than giving them free rein. The man who is a slave to his appetites is, we should intuitively grasp, unfree—and indeed radically so, unfree in the worst possible sense. To grow into maturity, and true freedom, is to learn to say “No” to the vast majority of pleasures, promptings, and opportunities that come along. What then are we to make of consumerism, of a “free market” that tries to give us as many options as possible, and keep us forever browsing, sampling, purchasing and replacing restlessly and compulsively?

In fact, advertisers know well that the ideal consumer is a child, since children are quite poor at distinguishing between different kinds of desire and unable to resist acting on impulses. But since children don’t have much disposable income, adults must be conditioned to think and act like children. Hence the modern market economy’s constant campaign (intensified exponentially by digital technology) against what has long been one of the basic conditions of “adulting”—deferred gratification. Increasingly unable to restrain our irrational desires, or even to distinguish rational desires from irrational ones, more and more of us are entering our twenties, thirties, or even forties in an essentially childlike state of immediate impulse-gratification. Needless to say, such childishness is not conducive to the profound self-denial and deferred gratification required by marriage and child-bearing; little wonder, then, that so many developed societies are facing demographic collapse.

Now, I am profoundly grateful for a market economy that has provided indoor plumbing and electric lights, gradually turning luxuries into staples by responding to consumer demand. But here’s the problem: the market economy is built on the ideal of ever-increasing consumption, and there are built-in biological limits to what any human being can consume in the traditional, literal sense (i.e., food and drink). Thus continued economic growth requires an acceleration in the rate at which products are used up, transforming formerly durable goods like furniture or clothing into consumables that we expect to replace within a few years or a few months. Electronics are often built with “planned obsolescence” in mind, as Apple or Google seeks to convince you that a perfectly functional smartphone must be discarded in favour of one with more camera lenses or fewer buttons. Even better than planned obsolescence is the manufacture of new wants or desires—a process that is most successful when products are geared less toward finite biological needs and more toward our seemingly boundless psychological needs. The most effective products are those that create more desires even as they seem to meet them, whether these be traditional addictive substances like alcohol or nicotine, or the powerful addiction machines of social media. These offer to assuage our loneliness and depression but tend to intensify such feelings the more we use them. The result is not freedom but slavery.

It is this economy of “hacking” that Clare Morell and I explored in our mega-essay for The New Atlantis a couple weeks ago: left to itself with no moral or legal guardrails, the market will tend to reward us for enslaving ourselves, and handsomely reward unscrupulous entrepreneurs in the process. Here, as elsewhere, genuine freedom requires limits—best of all, the internal limits and social norms cultivated by a moral and religious people, but failing those, the outward incentives, constraints, and punishments of law and public policy.

I hope you’ll take a few minutes to read the whole essay at Comment, and if you enjoy it, you can look forward to a lot more writing from me on economic topics in the year to come!

Coming Soon: Dignity and Dynamism

I’m excited to share that later this month—February 24th, in fact—I’ll be joining a group of distinguished panelists at the American Enterprise Institute to discuss and debate our new project, “A Future for the Family.” The event, “Dignity and Dynamism: The Future of Conservative Technology Policy,” will feature my collaborators Michael Toscano and Clare Morell, as well as interlocutors Leah Libresco Sargeant (Niskanen Center), Christine Rosen (AEI), and Ryan Streeter (Civitas Institute). And it will be headlined by Katherine Boyle, general partner at Andreesen Horowitz, one of the leading Christians in the advanced tech industry. If you’re in the DC area, I hope you’ll make plans to join us!

Get Involved

If you like this Substack, please spread the word with others. For now, this Substack will be totally free, but if you like the work I’m doing, please consider donating to it here by supporting EPPC and mentioning my name in the Comments.

If you have any questions or comments or pushback on anything you read here today (or recommendations for research leads I might want to chase down), please email me (w.b.littlejohn@gmail.com). I can’t promise I’ll have time to reply to every email, but even if you don’t hear back from me, I’m sure I’ll benefit from hearing your thoughts and disagreements.

Much of what you call consumerism is enabled by distorted consumer credit markets, which themselves are created by unsound money.

Imagine if the government abolished false weight and measures; i.e. manipulating markets with fiat currency and the fed's controls.

What would happen to consumer credit?

Let's not take statins for our high cholesterol, when in fact we need to eat our vegetables. There's only a handful of intrinsically immoral goods and services in the bible. No warnings against "consumerism", only false weights and measures.

Jesus invented wine knowing people would get addicted to it and it would be abused by people with no self control.

If the power dynamic between poor people in developing countries and the existing industries in those countries is really a problem, there's only two possible solutions:

1) make it illegal for those industries to hire

2) have open borders and truly free labor markets

One of those is the biblical solution, the other isn't. One requires the state assuming they have control over private property; the other eventually results in smaller and smaller gaps in the power dynamic.