One rarely hears much talk about “sin” anymore—not even from pastors. Not only liberal mainline pastors, but increasingly evangelicals, are more likely to talk about our “brokenness” than our sins. This can sometimes be a convenient evasion of responsibility, a failure to reckon with the reality of our own deeds—after all, while I am apt to feel guilty for sinning, who can blame me for being broken? That said, this language does capture an important insight that is central to the Augustinian tradition and the biblical testimony: that we are not simply people who do individual bad things, but we lie under the power of evil, as a crushing, warping burden that affects everything we do. We are genuinely broken—and yet guilty for that brokenness too. And the sense of guilt compounds the burden that thwarts our action.

Today, we face many threats to freedom, but the greatest threats of all are those which have not changed in millennia. All true freedom must start by resolving the problem at the heart of human existence: the alienation between God and man due to sin. If freedom is, as I have defined it, “the capacity for meaningful action,” then no wonder the Scriptures describe sin as slavery; for sin strips us of this capacity, separating us not only from God, the source of all ultimate meaning, but also from ourselves and our own purposes.

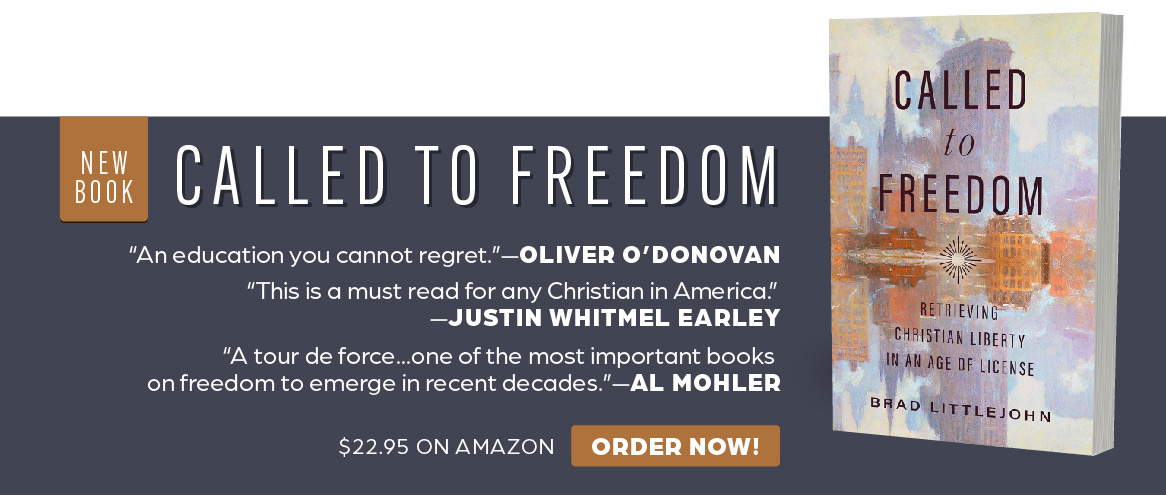

But we must be clear that there are two distinct problems here. There are individual actions of sin, which represent a bondage of the will to false notions and disordered desires. This bondage creates a moral slavery that good teaching and good habits can partially overcome but from which only the sanctifying work of the Spirit can truly free us. I consider this problem in chapter 3 of my book. The more fundamental problem, however, which is addressed by God’s gracious act of justification, is that we live in a condition of sin, under the power of sin, resulting in a spiritual bondage from which Christ alone can set us free. In chapter 2, summarized in today’s post, I consider the nature of this bondage and how the gospel liberates us from it.

The power of sin, I argue causes us to lose our freedom, our capacity for meaningful action, in three main ways: forgetfulness, futility, and fear. With the first, forgetfulness, sin cuts us off from our past, which provides us a sense of agency. Indeed, there are few experiences more disorienting and terrifying than being told we have done something of which we have no recollection. Yet if the past is a source of guilt, as it is for every sinner, we may seek to escape from it, hiding ourselves and dulling our memories in fresh acts of sin. Drugs and alcohol are simply the most vivid forms of such self-obliteration. The momentary “freedom” of such escape is indeed a Faustian bargain; the individual may evade the burden of painful responsibility but at the cost of losing a unified selfhood.

Second, there is what I have called futility, by which the present itself is rendered unintelligible to us. This can take several forms. Often, we can still form purposes, but we feel totally unable to realize them. Whatever good we seek to do, we do not do; it is as if some alien power has co-opted our mind and body. Other times, we succeed in achieving what we thought we wanted, surrounding ourselves with pleasures and achievements, only to find that they too are empty vapor—the constant theme of the book of Ecclesiastes. Either way this futility, whether the result of sin, external circumstances, or indeed chemical imbalances, can develop into the phenomenon of depression, which in extreme forms can result in an almost total paralysis of agency; an individual in such a state becomes convinced that there is no point in trying to act. Or perhaps “convinced” isn’t even the right word, implying as it does a free pathway of reasoning. Those locked in the throes of depression can experience a numbness that suffocates thought itself.

By the last, fear, we are blockaded from the future because of our terror of what lies ahead. Indeed, it is worth stressing that the great majority of what we ordinarily call “coercion” is strictly speaking just intimidation, the threat of future harm. I say “just” intimidation, even though it is in many ways more crippling than true coercion. If I am in chains, I may be physically compelled to go from point A to point B, but my mind may be free all the while—to scheme of escape, to sing hymns of praise to God like Paul and Silas, or simply to take in the beauty of my surroundings. If, however, I am cowed by fear of death or torture, I may find myself unable to think straight, unable to form any purposes beyond the current moment.

The Gospel offers itself as a solution to all three unfreedoms. Beginning with the last, it sets us free from the fear of death by silencing the law’s voice of condemnation: trusting in Christ’s righteousness rather than my own, I can face death unafraid and even joyful, confident in the resurrection. This was the world-transforming power of the early Christian martyrs.

It also sets us free from the attempt to find worth or meaning in the value of our own works. They have none in themselves, but clothed in the righteousness of Christ, our deeds are rescued from futility: “our labor in the Lord is not in vain.” Our imperfect works are made perfect; our transient deeds may fall into the soil and die, but they rise again to bear fruit thirty, sixty, and a hundredfold.

The freedom of a Christian also rescues us from forgetfulness. Sin drives us to self-deception, tempting us irresistibly to see ourselves as victims, rather than as genuine agents of our evil actions. Repentance is impossible without a true reckoning with the past. This is why, for Luther, the gospel is always preceded by law, a word of condemnation in which we are forced to look in the mirror and tell the truth about ourselves. Only when we know, and own, the depth of our own bondage can we turn to the gospel and be free of that bondage by accepting the alien righteousness of Christ, which cancels the believer’s past sin but only insofar as the believer remembers that this is the case—that is, that he or she really was truly under condemnation without Christ.

Too much Protestant theology nowadays has taken the good news of justification as a casual starting point, rather than as a hard-won conclusion. Christians are exhorted to celebrate their freedom in Christ, to shrug off any feelings of guilt, and to look on God as full of grace only, never wrath. Any reminder that sin deserves damnation is treated as an intrusion of Pharisaism. But this simply cheapens grace and takes it for granted. No, the good news is only good news against the backdrop of bad news about our condition without Christ, and if we allow ourselves to forget that, we will never experience the true freedom of a soul ransomed from the jaws of the dragon by the Savior who is at the same time the soul’s bridegroom. As Luther says, “Thus the believing soul by means of the pledge of his faith is free in Christ, its bridegroom, free from all sins, secure against death and hell, and is endowed with the eternal righteousness, life, and salvation of Christ, its bridegroom.”

The spiritual freedom of justification, I argue, must not be confused with moral freedom, as if there were now no need for the long, slow disciplines of sanctification. That is the error of antinomianism. But neither must it be confused with political freedom, which leads to anarchism, implying that just because we have been inwardly set free from the condemnation of God’s law, we have been outwardly set free from any obligation to obey human law. As Richard Hooker says, “[This] opinion, albeit applied here no further than to this present cause, shaketh universally the fabric of government, tendeth to anarchy and mere confusion, dissolveth families, dissipateth colleges, corporations, armies, overthroweth kingdoms, churches, and whatsoever is now through the providence of God by authority and power upheld.” The corporate liberty of churches, schools, and nations all rests in their ability to limit the outward individual liberty of their members, even while continuing to respect the inward liberty of their consciences. Too often today, “Christian liberty” is invoked as a get-out-of-submission-free card, destroying this corporate liberty and the ability of communities to grow in virtue together.

If you’re interested in more about how all these different kinds of liberty hold together, and how spiritual freedom, rightly understood, serves as the foundation of all other freedoms, I encourage you to check out the book!

This is the second of a series of posts which will preview each chapter of my new book, Called to Freedom: Retrieving Christian Liberty in an Age of License. You can buy it now from Lifeway or Amazon.

The Book Zone

Here over the coming weeks I’ll be keeping track of book-related publicity and publications.

Reviews

David Vandrunen, “Would You Rather be Free from Sin or State Regulation” (Christianity Today)

Grant Sutherland, “‘Called to Freedom’…but what does that mean?” (Mere Orthodoxy)

Essays/Interviews

“The Illusion of Freedom in a Digital Age” (Digital Liturgies)

“Political Freedom Between Right and Rights” (Mere Orthodoxy)

Podcasts

Speaking Gigs

At Pietas Classical School (Melbourne, FL, January 24)

At Church of Our Savior Oatlands (Leesburg, VA, January 26)

“Thinking Christianly About Freedom” (Washington, DC, February 5)

“Christian Liberty or Godless License” (Greenville, SC, February 18)

At The Field School (Chicago, IL, March 1)

At Calvary Memorial Church (Oak Park, IL, March 2)

At the North Carolina Study Center (Chapel Hill, NC, April 4)

At the University of Northwestern (St. Paul, MN, April 10)

In Case You Missed It…

January was a wild whirlwind month for me, which saw not only the publication of Called to Freedom, but three major collaborative efforts related to my new tech policy work. I’ve had a number of folks say they had trouble keeping up, so here’s a recap of key publications in January.

Protecting Kids from Porn: As you know, I’ve been working the past few months with my colleague Clare Morell and a growing coalition across many organizations to build momentum for the new effort to protect kids from porn and online sexual exploitation—above all through the simple, commonsense step of requiring pornography websites to verify the ages of anyone accessing the sites. In addition to our amicus curiae brief in November, Clare and I wrote a feature article for the latest issue of First Things, “Parents Can’t Fight Porn Alone.” We also participated in a number of events around the Supreme Court hearing of the case, which I wrote about at WORLD Opinions and summarized here on Substack. Below are my remarks from the rally:

“Stop Hacking Humans” (The New Atlantis): In another collaboration, this one also with Emma Waters, Clare and I situated the fight over online porn within a much broader framework, arguing that so many of our technologies today, rather than serving or healing human nature, instead seek to hack the human person. This is not merely the result of bad ideas, but also bad economic incentives; while a spiritual and metaphysical renewal is needed, so is better public policy. Our hope is that this essay, spanning everything from IVF to iPads to euthanasia, can offer a touchstone for conservative thinking about technology going forward.

“A Future for the Family” (First Things): An even larger collaboration, this one led by Michael Toscano of The Institute for Family Studies, and including me, Clare, Emma, and Jon Askonas, bore fruit in a comprehensive blueprint for how conservatives should govern technology in support of the American family. Published last week with over two dozen high-profile signatories, the statement is part of a larger, longer-term project to reframe thinking about tech on the Right, which will be housed at afutureforthefamily.org (you can also now add your signature to the statement there). I also attempted to contextualize the statement in a column for WORLD Opinions, “The Family and Technology.”

Two other essays: I also published two other columns on related themes at WORLD Opinions during the month: “Remaining in Neverland” and “Where TikTok Stands.”

Get Involved

If you like this Substack, please spread the word with others. For now, this Substack will be totally free, but if you like the work I’m doing, please consider donating to it here by supporting EPPC and mentioning my name in the Comments.

If you have any questions or comments or pushback on anything you read here today (or recommendations for research leads I might want to chase down), please email me (w.b.littlejohn@gmail.com). I can’t promise I’ll have time to reply to every email, but even if you don’t hear back from me, I’m sure I’ll benefit from hearing your thoughts and disagreements.