I Feel Like I'm Taking Crazy Pills

Moving the Overton Window in an age of legalized exploitation

I am known in many of my Signal chats as something of a gif connoisseur. It is a distinction that I quite pride myself on (*insert Michael Scott bowing gif*), despite my generally jaundiced view of digital culture. Perhaps the well-chosen gif is something like our version of the Homeric simile, rich with allusion and irony? In any case, one of my all-time favorite gifs, one particularly apropos to the age in which we find ourselves, is the Will Ferrell from Zoolander “I feel like I’m taking crazy pills” gif.

I found it repeatedly coming unbidden into my mind last Wednesday as I attended the “Attention Economy” event at the Federal Trade Commission.

Don’t get me wrong; the event was excellent—the organizers and the panelists, many of whom I have gotten to know over the past year through my work on child online safety, did a superb job. It was deeply heartening to see such a major federal institution, the agency charged above all with ensuring that the free market remains free from predation, focusing its own attention with laser sharpness and righteous indignation on the grotesque evils of surveillance capitalism and Big Tech’s exploitation of America’s children over the past two decades.

If you think those are strong words, consider one anecdote that stuck out at me, from Senator Katie Britt’s fiery speech: a few years ago, a Meta sales team prepared a slide deck for corporate advertisers boasting of how, with their detailed data on young users, they could help advertisers not merely target ads to particular user profiles, but at particular moments in time depending on the mood of the user. Anxious or depressed users, they explained, were particularly susceptible to the suggestion that they should buy something to make them feel better. The advertisers were duly impressed, and one went right ahead and purchased a targeted ad for beauty products that would be shown to 12-year-old girls right after they’d deleted a string of selfies on Instagram. Never mind that federal law, COPPA, prevents companies from even collecting data on users under 13—the companies just get around that by encouraging users to lie about their age and then pretending that they have no other data points to go on. And of course, don’t even get me started on the brain-warping porn for which even mainstream platforms like Instagram serve as conduits.

The speakers and panelists last Wednesday did an admirable job of shining a spotlight on these evils, on the perverse policy incentives and legal precedents that have enabled them, and the remedies available to policymakers to protect our youth and strengthen the hand of parents. Why then did I feel like I was taking crazy pills?

As the speakers moved from a catalogue of evils to a list of suggested solutions, I couldn’t help but feel that there was an almost comical disproportion between them. For instance, Sen. Britt mentioned a proposed federal law (which of course has not passed) that would require social media apps to have pop-up messages when you opened them, with warnings about how addictive and potentially harmful their feeds were. Can you imagine any 12-year-old girl or 17-year-old boy opening TikTok, seeing such a pop-up message, and saying, “Well gee, yikes, never mind then. I guess I’ll go read a book instead”? I recognize that the journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step, and that if Big Tech is our era’s Big Tobacco, we should remember that some of the first forward steps in that war began with the surgeon general’s warning. There is something to be said for admitting out loud what we all know to be the case. But still—surely we can be a tad more aggressive?

Or consider the case of AI chatbots. I was encouraged to hear several of the speakers raising this new issue as an urgent threat, highlighting just how addictive the startlingly lifelike interaction and the relentless love-bombing of these bots can be, especially for young users who don’t really have the critical faculties to understand what it is they are dealing with. Many of course have now heard the story of the 14-year-old boy in Florida, Sewell Setzer, who was seduced and ultimately lured into suicide by a Character.AI bot, and we can expect many more stories in future years if these companies are not held accountable for their product design. More disturbing, though, than platforms like Character.AI, where users must at least go in search of fictitious conversation partners, is the fact that mainstream social media platforms like Facebook are deploying ridiculously life-like chatbots as part of the standard user interface package. This makes a mockery of existing parental controls, which are based on the idea that parents can block access to apps with harmful content. When the apps pose to parents as one thing (enabling their children to connect to their actual real-life friends) and then quietly release software updates doing something else entirely (encouraging children to lose themselves in relationships with artificial friends), that’s just plain deception. Perhaps, it was suggested, the FTC could use its consumer protection authority to require more disclosure to parents about AI chatbots on platforms. That would be a nice step, for sure. But why exactly are we allowing companies to purvey reality-warping, emotion-hijacking, education-destroying AI bots to under-18s in the first place? I struggle to find any reason why a minor—who cannot buy Sudafed, smoke a cigarette, or (until 16 at least) drive a car—should be handed the world’s most powerful technology in the palm of their hand without parental supervision.

The ultimate “I FEEL LIKE I’M TAKING CRAZY PILLS” moment, though, came in the discussion of deepfake pornography. Panelists discussed the fact that there are now dozens of “nudify” apps, available through smartphone app stores and often easily-accessible by under-18s, that allow users to snap a photo of a classmate, or simply download their pic from social media, and run it through an app to remove as many articles of clothing as they like. That, of course, should be horrifying enough, especially to any parent of a daughter, but of course it doesn’t stop there. Such deepfake nudes are regularly circulated among students for revenge, blackmail, or just cold hard cash. Or they are posted publicly on social media or porn sites. With the technology rapidly “improving” (if that is the word for it!), you can now, at least for a fee, generate deepfake videos of a classmate performing a sex act.

Now, at this point the panelists paused to celebrate the wonderful achievement of the new TAKEITDOWN Act, a landmark in anti-pornography legislation. According to this law, which recently passed Congress almost unanimously and was signed into law by President Trump, anyone who is a victim of nonconsensually-shared sexual imagery (whether old-fashioned revenge porn or deepfakes) now has some clear legally-defined rights. If they discover that it has been shared on a digital platform without their consent, they can submit a notice to the platform, explaining that they are the person whose image is being depicted, that they have not authorized it, and that they want it taken down. The company then has to remove the image within 48 hours and take steps to prevent it being re-uploaded, or face stiff penalties. Great, right? A shining example of bipartisan collaboration in defense of decency and common sense, right?

Well, sure, but, forgive me if I’m taking crazy pills…but, um, what about those nudify apps? Is it just me or did we just leave the supply side of this equation totally untouched? It’s as if a chemical plant were dumping vats full of deadly toxins into a river, poisoning everyone downstream, and we had now passed landmark legislation authorizing those citizens to submit a complaint and have the toxins removed from their water by local authorities within 48 hours—while continuing to allow the plant to keep pouring in as many toxins as they want. So I ask you, my fellow Americans: what possible justification is there for allowing developers to create such an app? What possible justification is there for allowing app stores to sell them? We are talking about an application whose developers went into a pitch meeting with investors and said, “Yeah, so we have a great business plan: we’ve created an app for generating non-consensual sexual imagery, a great deal of which will be child pornography.” That is literally the sole purpose for the existence of these apps. (Ok, to be fair, when I vented this to a friend who is a veteran of fighting these companies, he said: “Well what they’ll say is that they’re meant to be used among consenting adults—your girlfriend could text you a clothed picture of herself and say, ‘Hey, feed this into your Undressr’” *insert Dr. Evil Right gif*)

I get it that this is supposed to be the land of the free and we have the First Amendment and all that, but seriously, folks! To quote Justice Samuel Alito: “While individuals are certainly free to think and to say what they wish about ‘existence,’ ‘meaning,’ the ‘universe,’ and ‘the mystery of human life,’ they are not always free to act in accordance with those thoughts.” Or to rephrase, “While individuals are certainly free to imagine you naked, they’re not free to actually make you appear naked.” Nothing demonstrates the emptiness of the so-called #MeToo movement more than the fact that venture capitalists were eagerly pouring their millions into these apps even as women were marching against sexual abuse.

I understand that if you want to live by the rule of law and court precedent, then change often has to happen slowly and incrementally. Indeed, we are currently eagerly awaiting a possible reversal of an insane court precedent—one which decided back in 2004 that the rights of adults to access hardcore pornography without proving their age should trump the rights of children to be protected from such content. The tide does seem to be largely flowing in the right direction. On the other hand, we cannot afford to fight this battle out over 40 years, the way we did with the War on Big Tobacco. The harms of smoking are generally displaced decades into the future; the harms of addictive and sexually explicit media are immediate. The harms of smoking disproportionately affect the oldest; digital harms disproportionately affect the youngest. The harms of smoking may kill the body but leave the soul untouched; digital harms destroy the soul. And tobacco technology was basically stationary by the 1950s—digital technology, however, is an ever-evolving hydra that keeps sprouting clever new tools for civilizational suicide.

We hear a lot these days of Trumpian politics about how if you want to, “you can just do stuff”; you can “move the Overton window” and completely change the policy option set. If so, let’s find a way to do so on the issues that are most urgently affecting the largest number of Americans, the evils of the pornographied attention economy. With a coalition of outraged feminists, principled social conservatives, and parents ready to fight for their children’s future, anything ought to be politically possible.

A “Future for the Family” Reunion

I had a blast Friday morning (seriously—I’m inwardly beaming, whatever my outward facial expression!) presenting on a panel on “Technology and Human (De)formation” at the Academy of Philosophy and Letters conference in College Park, MD, alongside my fellow “Future for the Family” co-authors, Clare Morell and Jon Askonas. If you’ve already forgotten about the “Future for the Family” initiative, amidst the bewildering churn of the news cycle, now would be a good time to remember it. The techno-libertarians are already quaking in their boots that with Musk now out of favor, “the people and orgs behind that radical "Future of the Family" anti-technology manifesto published a few months ago will also now start to have far more sway in the Trump admin and halls of Congress.” Although the FFF project has been on a slow burn while most of us started new jobs, we’ll be turning up the heat this summer, so stay tuned!

The panel itself was one of those wonderful occasions where you come with your own manuscript prepared to dispense knowledge, but find yourself feverishly jotting down notes from your fellow panelists’ talks. Jon in particular had some profound insights about AI that may find their way in some form onto this Substack in the near future. My own remarks began thusly:

“If you’re like many Americans, odds are when you woke up this morning, you opened your laptop and checked your email…then saw an interesting Substack post in your inbox, skimmed it, and followed some links…and half an hour later, found yourself watching some dumb news clip about a celebrity, your morning coffee still in the pot and your morning Bible time window rapidly closing. Later in the day, perhaps you found yourself impulsively pulling your phone from your pocket and opening two or three apps for no particular reason, then putting it back until a few minutes later you felt a phantom buzz on your thigh and whipped your phone back out in response to an imaginary notification. . . .

But our individual aimlessness when it comes to technology is symptomatic of a society-wide syndrome. For many decades now, Americans have rarely asked whether a new technology should be developed and deployed. If we can do it, we should, right? You’re not against progress, are you? Of course, the question is nonsensical, because “progress” must always be measured relative to a destination, but our innovators do not seem to have one.”

I’m sure the full version will be published in some form somewhere this summer, so stay tuned for that.

Speaking of Technology…

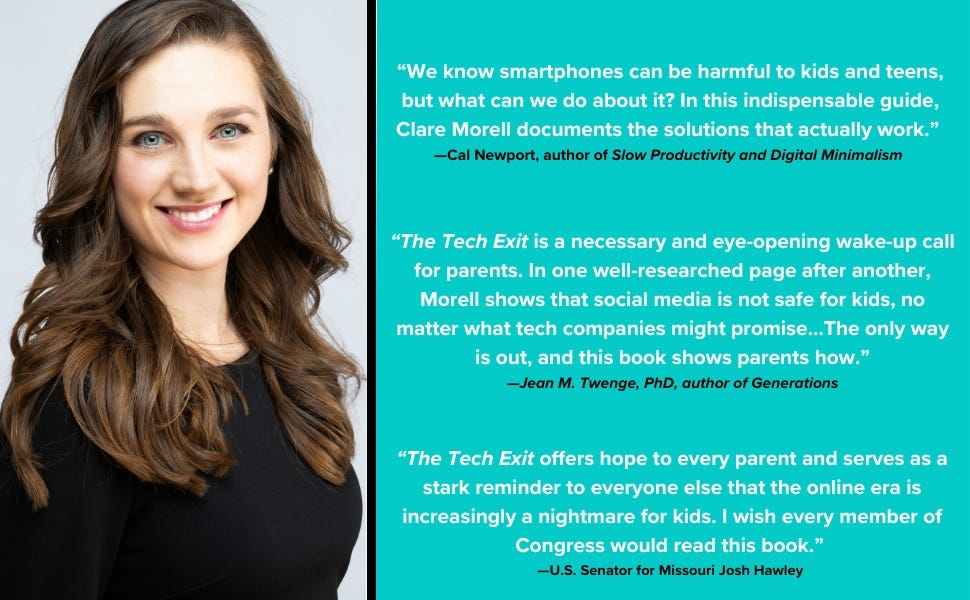

…and of Clare Morell, in case you’ve been living under a rock the last week, her new book, The Tech Exit: A Practical Guide for Freeing Kids and Teens from Smartphones, is now out and making waves in every direction.

Here was my brief review, posted on Amazon:

This is a clear, bold, timely, essential book, facing head-on the great civilizational crisis of our time: the disastrous consequences of the mass social experiment we have conducted the past twenty years on ourselves, and above all on our children. The Tech Exit pulls no punches in diagnosing the disastrous consequences of screen addiction, social media saturation, and the torrent of sexual exploitation and self-exploitation these platforms have unleashed.

But it does much more than that: it offers an extremely practical, down-to-earth how-to manual on how to reverse the technological tide and rediscover how to live with your children as so many families lived for centuries before we started trying to turn them into cyborgs. Although, as someone working in this field myself, I was unsurprised by most of the studies Morell cites or even many of the suggestions she makes, I did find myself taken aback by just how practically actionable her suggestions were. This really isn't rocket science--and millions of parents are already living these principles. I found myself so encouraged by her stories of families that had found (as my wife and I have found in our own home!) that adjusting to a low-tech lifestyle in a high-tech world is not nearly so hard as it can look, as long as you proceed with determination, clarity, and above all, a community of other parents willing to practice the same norms.

The book is also extremely readable, written in a conversational style with lots of engaging stories and testimonies.

If I may quibble, I think I have two points of minor criticism.

The first is that Morell is sometimes a bit overreaching in her claims—for instance in the final chapter where she somewhat jarringly proclaims "to address this underlying crisis, we need to exit digital technologies completely." Granted, in context she is referring to childhood, but even so, this claim goes beyond what seems to be supported by the rest of her argument, and I'm not sure that she quite means it so unequivocally. There are many forms of digital technology, and many different ways of using them. To be sure, the ones we use most have often been the most corrosive, addictive, and dysfunctional forms. But having detoxed from such products, there is no reason that we cannot judiciously and strategically use digital tools for genuine educational or friendship-building purposes. For instance, video games can be dangerously addictive, but they can be a great camaderie-building activity for a bunch of 12-year-old boys in the basement at a birthday party. The internet is a dangerous place, but email and instant messenger can provide a wonderful way for teens to nurture friendships with connections from summer camp or online classes. Morell constantly refers to "social media" in sweeping terms but without really defining it. If she means TikTok, Instagram, Snapchat—the pre-teen poisons of choice these days—I'm completely with her. But especially for the teen years, there are forms of online media that are, well, social, that can be a healthy part of building a friendship network.

The second related point is that I think the book would have benefited from a chapter or two at the beginning laying out the problem in broad terms: what healthy childhood development looks like, and the various ways we are interfering with that. This would've provided a clear foundation and set of definitions for all of the prescriptions that follow. However, this valuable discussion is saved for the very last chapter of the book, where she says, "We can determine what is right for our kids in regard to screens only after we answer the question, What are people—and in particular what is childhood—for?" Exactly. But if so, perhaps these questions should have been asked and addressed at the beginning of the book? But then, other readers may be less philosophically-minded, and appreciate Morell's decision to simply jump straight into practicalities.

These minor quibbles aside, this is definitely a fantastic book for your church or school book group, if you’re looking to build a critical mass of low-tech families in your community. Buy a copy now!

I appreciate your comments on 'The Tech Exit' -- this brings a bit of balance to the completely enthused review by Brad East at CT. Anyways, we'll be getting a copy for sure.

Oh, as a fellow gif-lover, I send you my Cpt. Kirk nod of approval.

Great article. Lawmakers in the States and elsewhere in the West generally drag their feet when it comes to porn. As you said, The “Take It Down” act is unbelievably weak — once an image is uploaded, it can travel to every corner of the internet. The best solution to any problem is prevention, and that means taking down those nudifying apps in the first place. Why that hasn’t happened yet is beyond me.