Note: Last night I had the pleasure of “debating” Kevin Vallier (author of All The Kingdoms of the World) at GWU’s Illiberalism Studies Institute on the question “Why is liberalism becoming illiberal?” We had a delightful and mutually illuminating discussion. Below are my opening remarks:

The question I have been asked to address is “Why has liberalism become illiberal?” Of course, within this question, a great many things are presupposed. For one, the question presupposes that liberalism has in fact become illiberal—at least in many quarters, and to some extent. This is no accident; Kevin and I discussed when this panel was first suggested and discovered that we both agreed that this is a plausible description of at least many recent trends. But, we must dig deeper to determine what we mean by the key words in this sentence. What do we mean by “illiberal,” most obviously? But clearly, even this question cannot be answered except with reference to its opposite: what, then, do we mean by liberalism? I must necessarily be brief, but my fuller thoughts, which I will draw on here, can be found in an essay I published last fall in National Affairs, “The Four Causes of Liberalism.” In it, I use Aristotle’s “four causes” as a framework for understanding different accounts of liberalism.

Very briefly, I suggest that “material cause” liberalism is concerned with what is political society fundamentally composed of? And it answers, “why, individuals, of course,” in contrast to pre-liberal or post-liberal accounts which stress group solidarities, such as families, tribes, or even the nation as the units of political society. “Formal cause” liberalism answers “how is political society organized?” and its answers draw on ideas like constitutionalism or the rule of law, over against ideas of personal power or authoritarianism. “Efficient cause” liberalism is concerned with how political society operates, and stresses the use of persuasion and toleration in the face of difference rather than using coercion and exclusion to achieve its will. Finally, “final cause” liberalism answers the question, what is political society for? by rejecting the idea that there should be a unitary answer; rather, it exists simply to facilitate individual lifestyle experimentation among its members as they each pursue their own vision of happiness.

Now, there are clearly signs that the apogee of liberalism has passed on all four fronts, but there is no time to discuss all four. Rather, let me focus on the first and third, and I’m happy to touch on the others in discussion if desired. I’ll flesh out a bit what I mean first by “material cause” liberalism, what evidence there is that we are becoming less liberal on this front, and why that might be. Then I’ll do the same with “efficient cause.”

Material Cause Liberalism

On many accounts, what is distinctive about liberalism is its focus on the autonomous individual, “independent and free any obligations that have not been expressly chosen,” as Mark Mitchell puts it in The Limits of Liberalism. Most past societies would have found this strange, stressing instead the unchosen bonds of dependence with which we came into the world and which continued to structure our social relations. Entities like the family loomed larger than the individual, and provided the basic building block and negotiating unit for political society.

There is ample evidence that we are in the midst of some kind of reaction to or retreat from such a vision of liberalism. Across the world, ethno-nationalist movements have gained considerable traction, even in the most liberal societies of Europe and the US. Indeed, we have witnessed a disturbing rise of race-consciousness and white identity politics here in America. In my own Protestant circles, the so-called “Christian nationalist” movement has encouraged voices that call for white European males to organize as an identity group and seek political power, and reject the liberal ideal of equal treatment for all fellow citizens.

Now, in part, it must be recognized, this is obviously a reaction to left identity politics, which has been utterly shameless in mobilizing group identities and encouraging people to vote by class or race. Many on the Right have essentially said, “Ok, if you’re going to play that game, we can play it too.”

But where does this illiberal impulse come from? I’d like to provide three answers:

First, it is in part at least a salutary reaction against one-sidedness. It really is the case that human beings are basically tribal in their fundamental instincts and more or less always have been. Even the most liberal societies generally only succeed in sublimating these instincts to the level of political parties or economic classes. People don’t want to be mere individuals; they want to belong. They recognize that they exist in relationships and have obligations they didn’t necessarily choose. To the extent, then, that liberalism denied human nature by pushing its point too far, a correction was inevitable.

Second, technology has played the role of an accelerant. Digital experience has helped fracture us further, pulling us away from the embodied, relational identities central to our humanity, and thus made us hungrier for some form of group identity. But it has also then responded to that hunger by creating artificial new forms of identity, algorithmically matching us up with “people like you” and reinforcing these affinities by putting us in echo-chambers. These new identities, however, tend to be somewhat ersatz and ephemeral, and often for that very reason, more intensely and irrationally clung to. In his legendary essay “The Internet of Beefs,” Venkatesh Rao argues that “We are not beefing endlessly because we do not desire peace or because we do not know how to engineer peace. We are beefing because we no longer know who we are, each of us individually, and collectively as a species…[We are faced] with the terrifying possibility that if there is no history in the future, there is nobody in particular to be once the beefing stops.”

Finally, let’s consider the role of Christianity. If it is true that human beings are naturally tribal, what is it that overcame this natural instinct? Historians Larry Siedentop and Tom Holland have both compellingly argued recently that it was Christianity, which Siedentop goes so far as to say “invented the individual,” demolishing ancient political visions that sacralized the family and tribe. On Christianity’s account, not only were individuals of profound political importance, but all individuals were in some important sense equal to one another, whatever their parentage or tribe. Christianity, however, did not deny the importance of group identities (the church itself was a powerful corporate identity) and unchosen obligations (most Christians began their membership in the church as baptized infants). Liberalism, however, radicalized Christianity’s individualist trajectory, but at the same time, cast itself loose from its Christian moorings, hoping to fly free from Christianity’s remaining illiberal elements. Instead we are finding that, on its own, liberalism cannot explain the dignity of the individual, and is crashing back down to earth.

Efficient Cause Liberalism

What then can we say about “efficient cause liberalism”? Since the liberal ideal is a society held together by consent, then I ought not do anything, and we ought not do anything together, unless we have agreed to it — ideally by virtue of rational persuasion, since that is the freest form of action available to us. The opposite of persuaded consent is coercion, and liberal societies have prided themselves, therefore, on their attempts to minimize coercion's scope and severity.

Here, too, we see signs of a retreat from this liberal ideal—less advanced, perhaps, than what I just noted with regard to individualism, but still distinctly discernible at least at the level of rhetoric, which could erupt into action at any time. We have witnessed a collapse in the norms of civility in public discourse, and a rapidly growing tolerance for violent and hostile rhetoric. Trump himself may be the greatest poster child for this, but it is clearly larger than his own personality, as evidenced in the recent episode when Vice President Vance publicly defended a DOGE staffer fired for his virulently racist tweets. Although words are cheap, and violent rhetoric has thus far remained largely rhetoric, we have seen an uptick in political violence, especially in the summer of 2020 and of course on January 6th. Of course, as the first example highlights, again we are dealing with a phenomenon on both ends of the political spectrum, not just the Right.

Where is this coming from? Let’s look at the same three factors:

First, again in part what we have is a reaction—perhaps not a salutary one, but at least an understandable one—against liberalism’s overreach and one-sidedness. Codes of political correctness clearly got out of hand in recent decades. First, we were told that words were a form of violence, and before long, that even “silence is violence.” Despite formal constitutional protections of free speech, many Americans felt that they were living under a stifling regime of censorship from elite institutions, which labeled any unpopular opinions as “hateful” and “violent” rhetoric. If we’re going to be accused of that anyway, many seem to have concluded, we might as well actually get the catharsis of doing it.

Second, the technological dimension. It is almost cliched now to say that technology has made us uncivil and intensified political polarization. But it’s no less true for that. Clearly, disembodied digital experience makes it far easier to lob vicious rhetorical grenades at faceless opponents, especially when you get the dopamine hit of lots of reactions, and especially if you can do it under a pseudonym. And of course, as mentioned above, the algorithms herd us together into echo chambers, intensifying polarization.

Finally, then, Christianity. Once more, our culture of persuasion and tolerance owes a vast amount to Christianity. Love of enemies, after all, is not exactly a default human impulse. It requires profound discipline and humility—above all, humility before the confidence of final divine judgment, in the face of which we can let go of offenses and “beefs,” and allow some of our conflicts to go unfought and unlitigated. The culture of persuasion also emerges particularly out of Christianity’s unique soteriology, which was especially sharpened in the Protestant Reformation. Almost every other traditional religion is built above all around ritual and public acts of piety. In such a religion, the presence of heretics or apostates is intolerable, and they should be forced to recant at the point of the sword. But if salvation is a matter of sincere faith, hidden in the heart, there is no point trying to compel right religion. This conviction led early modern Christian societies to what Oliver O’Donovan calls “a self-abdication instilled by their monotheistic faith...direct[ing] their members to become critical moral intelligences...answerable directly to God.” Which meant: it is not society’s job to coerce conformity. As Christian cultural influence has waned, is it any wonder that we should revert to more barbaric instincts? Once again, as liberalism has sought to fly higher than Christianity allowed it, condemning the church as too illiberal, it has found it has no wings of its own with which to soar aloft.

Similar points could be made, I believe, about “formal cause” and “final cause” liberalism as well, but I will stop there. And, as for what to do about this illiberalism? Well, fixing our problems is not simply a matter of retracing our steps; certainly, it is unclear how the tech genie can be put back into the bottle. And religious revival doesn’t come merely by snapping one’s fingers. But while we can only go forward, not backward, this map of how we got here at least gives us some idea of where to guide our steps. And we can at least begin by recognizing the extent to which liberalism’s own flight from reality invited the backlash by which it now seems so surprised.

Recently Published

“Stopping Sextortion” (WORLD Opinions): In recent years, cases of “sextortion” have risen 18,000%, the product largely of organized crime rings operating out of Nigeria and using mainstream social media to recruit both new perpetrators and target new victims. The playbook is simple: message a teenage boy out of the blue claiming to be a hot girl, chat him up until you get him to engage in explicit banter and share explicit images, and then reveal that you’re actually a professional criminal who needs money sent via Cash right now or else his friends, parents, and pastor will see the screenshot. Dozens of victims have committed suicide. Apps have the tools to combat this behavior, but have no financial incentive to try.

“Creating a Digital Age Gate” (WORLD Opinions): In just the last few weeks, a surging movement for “App store accountability” has gained extraordinary traction in statehouses across America, with Utah becoming the first state to enact this new legislation. The theory is simple: you can’t contract with a minor, so why are tens of thousands of apps doing exactly that, by having minors accept terms of service agreements signing away all their privacy rights? Closing this legal loophole could put parents back in charge of their kids’ digital lives, requiring parental consent for every app download or in-app purchase.

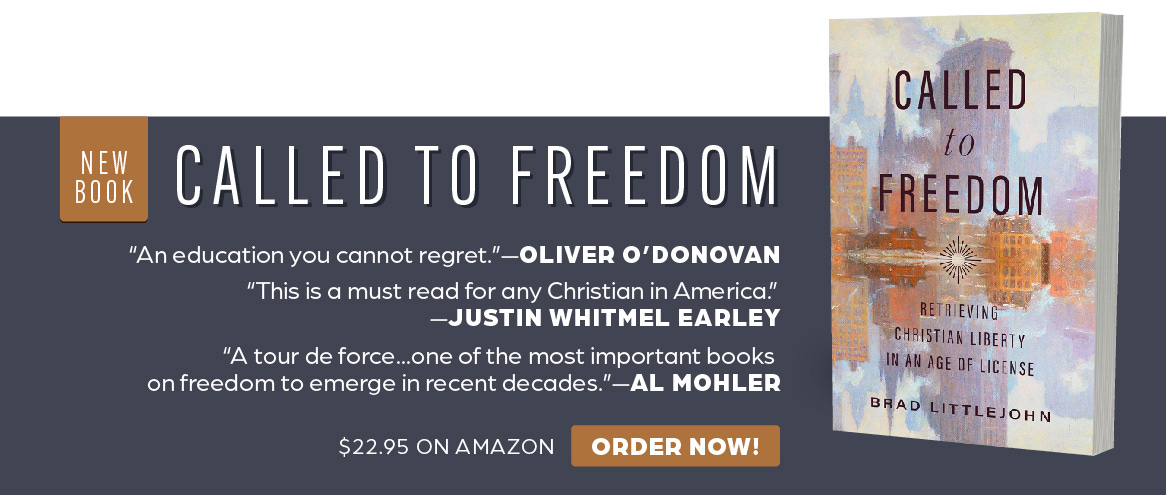

“A Vision of Freedom” (CPT Podcast): I’ve lost count of the number of podcast interviews I’ve done on my book, Called to Freedom, but this was a particularly good conversation with the folks at the Center for Pastor Theologians. Hope you’ll enjoy listening as much as I enjoyed talking. :-)

“When Technology Goes Too Far” (CFC Podcast): I also had a fantastic conversation with the Center for Faith and Culture, not so much on my book, but on my recent essay with Clare Morell and Emma Waters, “Stop Hacking Humans,” part of our larger Future for the Family project. It was a great interview—give it a listen!

Coming down the Pipe

“Family Formation and the Future: The Geopolitical, Cultural, and Legal Dimensions of Demographic Change” (forthcoming event at the Danube Institute in Budapest, 4/1): I will be speaking on how parents are mobilizing to defeat the porn industry.

“The Illusion of Freedom in a Digital Age” (forthcoming event at the Center for Public Christianity in Raleigh, 4/4): I’m looking forward to returning to Raleigh in a couple of weeks to speak on issues at the intersection of my writing on freedom and my recent work on technology. If you’re in the area, I’d love to see you there!

“American Ideals or American Idols? Thinking Christianly About Freedom” (forthcoming event at the University of Northwestern, St. Paul, 4/15): I’ll be visiting the Twin Cities on April 15th as what I think will be the last stop on my spring book tour. Should be a fantastic evening.

On the Bookshelf

A World After Liberalism: Philosophers of the Radical Right (Matthew Rose): This has been on the shelf for a while, but I finally read it these last two weeks. Riveting and beautifully-written; yet another case study in the phenomenon of Catholic prose being 10x better than Protestant prose. More substantively, though, Rose gives us a richly illuminating context for the recent rise of the “alt-right,” by surveying key radical thinkers of the 20th century who anticipated many of their key ideas. I was particularly struck by the profiles of Julius Evola and Sam Francis, in whom I recognized so many of the talking points that I’ve encountered among the seedier underbelly of the “Christian nationalist” movement in recent years.

All The Kingdoms of the World: On Radical Religious Alternatives to Liberalism (Kevin Vallier): Since I was going to be “debating” him, I figured I’d better start reading his most recent book, and what a joy it is to read. Vallier is another fantastic writer, and this sympathetic study and critique of Catholic integralism is essential for understanding the current postliberal phenomenon. I’ll confess: when I realized that the book wasn’t immediately relevant to the question we’d be debating, I set it aside for more urgent things, but I hope to finish it over the next week or two.

Are We All Cyborgs Now? Reclaiming our Humanity from the Machine (Robin Phillips and Josh Pauling): I’ve been told for several months I need to read this book, and it’s high time I got started. Hope to dig in starting this weekend.

Recommended Reads

“Our Great American Industrial Comeback” (JD Vance, Commonplace): It is a breath of fresh air to hear a sitting US Vice President who understands the economics of American prosperity so clearly. I do believe there’s some continued incoherence in suggesting that AI can somehow be deregulated and channeled toward human flourishing at the same time, but I suspect that this is less a mark of naivete than realpolitik. Vance must be smart enough to know that the guardrails for AI that he’s hinted at here and in his Paris speech will require serious attention if his aspirations for its beneficent effects are to be realized.

“How Anora Signals the End of Hollywood’s #MeToo Era” (Aaron Renn): “What does this all mean? Well, in short, it means that the simple reason that the #MeToo movement didn’t last is that powerful men didn’t want it to. Just like with hookup culture and prostitution and women in the workforce, men embraced the aspects of the #MeToo movement that benefited them (elevating female voices made them a lot of money with Barbie). But they won’t change anything that actually gets in the way of them getting what they want.”

“The Great Tech-Family Alliance” (Katherine Boyle, Tablet Mag): Katherine Boyle’s keynote address from our “Dignity and Dynamism” event at AEI was recently published in full. I have at least three significant questions/misgivings about it, which I may have occasion to publish before long, but still, the fact that such a leading representative of the Silicon Valley world is ready to reframe advanced tech in service of the traditional family—rather than merely “the empowerment of individuals” or grandiose aspirations for the enhancement of the species—is, as Ron Burgundy would say, kind of a big deal.

Support my Work

Since writing is part of what I do for a living, and you, my readers, appreciate that writing, I’ve recently added a paid subscription tier for those who want to support my work with a small annual or monthly contribution. If you’d like to see more about how our technological culture is reshaping our understanding of what it means to be human, what we can do as citizens to fight back, and what we can do as Christians to chart a better path, consider a paid subscription. Most of the content will be available for free to all subscribers, but the full archive and occasional member-only posts (including “podcasts”/audio posts) will be for paid subscribers only

Liberalism in 1776:

All men are "free" but not really, chattel slavery.

Liberalism in 1876:

All men are free, but Jim Crow

Liberalism in 1976:

No more Jim Crow.

Whether liberalism failed or not really depends on from what angle you look. Was it illiberalism that formally banished racism?