Stop Hacking the Human Person

A brave new world of technology requires a new approach to political economy

Today, my colleague Clare Morell and I are live at The New Atlantis with “Stop Hacking Humans.” This is a bold, ambitious, wide-ranging essay on technology, medicine, and political economy that addresses everything from IVF to Neuralink to pornography to euthanasia, and it reflects the work of many: in particular, Emma Waters of the Heritage Foundation contributed extensively to the material on reproductive and end-of-life technologies, although we weren’t able to list her as an author. Our basic thesis: from gamete to grave, today’s technologies have increasingly moved from healing human hurts and leveraging human capacities to hacking the human person.

Hacking, of course, is a term drawn from computer systems, and it is symptomatic of our tendency to re-conceive ourselves in terms of our own machine creations that we have begun to apply it to ourselves (consider the popular website, LifeHacker). A “hack” is any clever technological shortcut or cheat code, any way to bypass the ordinary structure of a thing in order to get the desired output sooner. Indeed, the ideal of “hacking” is at the heart of our technological culture, representing our relentless pragmatism, our continual quest to find the quickest, easiest path toward our destination. Never mind that when we arrive there, we often feel hollow and unsatisfied, like the video gamer who annihilates his competitors through a cheat code that grants him superpowers. If we’re feeling down, there’s bound to be a hack for that too. Even our theory and practice of medicine has been seduced by the “hacking” mentality, seeing healthcare itself as a series of “cool tricks” that make the doctor’s work more efficient and cater to the patient’s demands.

And yet for all this, the language of “hacking” retains overtones of violence. The word originally meant to cut into something or cut something off—as indeed we find today with “gender-reassignment surgery.” Unable to resolve the patient’s dysphoria, we resort to amputation, which as Oliver O’Donovan observes, “is certainly intended to do the patient good…[yet] it is not a medical good that it is doing her, but a social good. And to serve that social good, moreover, it adopts a procedure which is not even medically neutral, but manifestly injurious.” It represents an abandonment of the historic understanding of “first: do no harm,” the commitment of medicine to the goal of bodily health. Defenders will justify it on the grounds that bodily health is being sacrificed for the higher end of psychological health, but this is a far more elusive ideal, one that turns out to mean little more than the satisfaction of short-term desires, without regard for whether those desires can be integrated into an enduring form of flourishing.

The fate of healthcare in our technological age highlights the larger trend toward hacking the human person. Healthcare used to be ordered toward the good of health, which is to say the holistic proper functioning of an organism in accord with its nature. To heal an organism, therefore, is to (1) discern its objective and distinctive form of flourishing; (2) identify the disorder or lack that is interfering with it; (3) remove/reverse/repair the source of the disorder or fill the lack; (4) give the organism space to respond, adapt, and resume its path toward renewed flourishing. On this understanding, writes O’Donovan, “not everything to which people will consent, or which they will even demand, is the right thing for medicine to undertake.” For instance, “If I am too short to join the police force, too quickly winded to be selected for the Olympic team, or too forgetful to pass history examinations, it is not a matter of my doctor to deal with.” Or is it? Today, aided by Silicon Valley, we have begun to dream of genetic modifications that could make us (or at least our children) taller, faster, and smarter.

We have, in short, begun to hack human nature. When we hack, rather than heal, we 1) discern a real human desire or longing, and (2) identify a technique that could enable us to meet that desire, (3) bypassing ordinary human functions, (4) in a way that, while it may be pleasurable and often highly profitable in the short-term, threatens the long-term health of the individual and/or society. The hack offers a shortcut to a desired endpoint, but when we arrive, we often find that much of what we had sought has gone missing.

In the essay, we show how this basic logic of hacking has come to shape every stage of our lives: our approach to conception and birth, to child development, to sexuality and marriage, and to death (or the avoidance of it). At every stage, we have encouraged and embraced technologies that offer us shortcuts to enhancing our pleasure and freedom, or suppressing our pain, without regard to the constraints of human nature. Inevitably, such efforts may provide a short-term fix at the cost of greater long-term suffering for the individual or society as a whole—and yet we accept the bargain, trusting that there will always be another technology to treat the symptoms of the cure.

This argument, bringing together various spheres of bio-ethics and technology criticism that till now have often been treated as discrete issues, makes a major contribution to the current ferment on the Right, and offers the possibility of a unified agenda for assessing and governing our technologies—as we will spell out in a major statement of principles that publishes at First Things on Wednesday. However, the essay goes further, arguing that we must understand this regime of hacking as, at root, a failure of political economy, one that requires a re-imagining of conservative economics.

After all, a crude version of free-market theory, which many Americans have been seduced into applying to digital technology over the past three decades (allowing it to become the largest and most concentrated industry the world has ever seen), assumes that consumers are rational agents acting in their own self-interest to maximize their utility. But of course, common sense knows that most humans are thoroughly irrational, their wills often hijacked by impulsive desires for food, sex, and fame—fleeting pleasures that may well be at odds with their true flourishing. Left to our own devices, we tend to look for shortcuts to happiness: paths of least resistance that will gratify today even if they may come back to bite us tomorrow. And today, our devices are more than happy to provide such shortcuts.

Free-market theory, at one level, understands the possibility of such “market failures,” so that most people recognize there cannot be a truly free market in addictive products, which overwhelm our rational faculties to give us short-term hits that will harm us later. Depending on how addictive, and how harmful, we regulate or even ban such products. Till now, however, we have been strangely unwilling to do so in the digital realm, and we have also allowed the profession of healthcare to be overtaken by the logic of consumerism. Part of the problem is perverse incentives. In a political economy of hacking, there is money to be made twice over: in selling the product and in selling its cure. An unhealthy society, America has learned, is capable of generating a lot more GDP than a healthy one: there’s money to be made selling junk food, and money to be made on Ozempic; there’s money to be made on fentanyl, and money to be made on Narcan and rehab clinics; there’s money to be made on anxiety-inducing social media apps, and money to be made on therapy; there’s money to be made on online pornography, and money to be made on parental controls and filtering software.

Thankfully, however, if our political economy of hacking thrives on perverse incentives, there is room for a new political economy to reframe the choice architecture of innovation. The government can channel technology development in certain directions, towards human flourishing and strengthening the human family, and away from results that undermine these ends. When hacking the human person gets too easy, the state may have a role to say “No,” shutting doors to the harmful and lazy short-cuts. But this is not a “No” to innovation, only an invitation to try harder, to explore other doors. The market can and should do its magic—but within the moral constraints that we set for the protection of human nature and the human family. At the conclusion of the essay, accordingly, we offer a few practical policy suggestions for how we might begin to rein in our political economy of hacking.

I believe this is one of the most important essays I’ve ever had the privilege of working on, and I’m so grateful to my colleague Clare for her co-authorship, to Emma Waters for her critical contributions, to Jared Hayden of IFS for helpful research and suggested edits throughout, and to Ari Schulman and Samuel Matlack at The New Atlantis for committing to a truly insane publication schedule to get this out within the first week of the new administration! For the broader context of this project, see also Michael Toscano and Jon Askonas’s “Technology for the American Family” at National Affairs, and keep an eye on the First Things website this Wednesday!

Other Newly Published

“Where TikTok Stands” (WORLD Opinions): In my latest column for WORLD, I review the current topsy-turvy situation surrounding TikTok’s divestiture, and why President Trump has decided to try and throw the company a lifeline. Although my personal preference would be to see the app banned for good, a deal that involves divestiture to US investors will still help protect US national security and Americans’ privacy, and enable the app to be held accountable to follow applicable US laws.

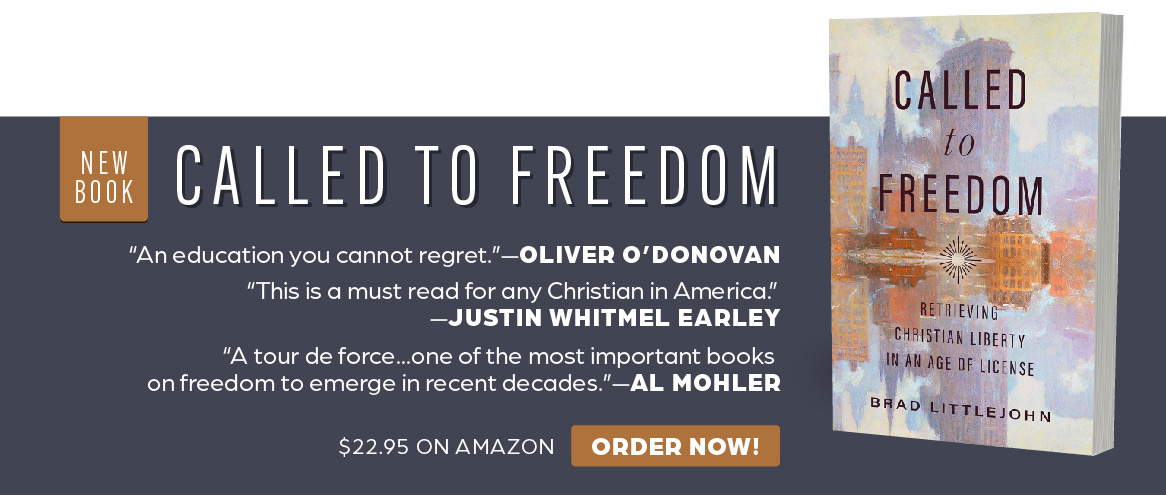

Called to Freedom Interview (History of Christian Theology Podcast): In this podcast interview with Chad Kim of St. Louis University, I explore a number of themes in my new book, Called to Freedom. We discuss why it is that some people de-convert from Christianity in search of greater freedom, how Augustine’s concept of the “the will” relates to freedom, and what my current work against the pornography industry in the Paxton case has to do with all this.

Coming down the Pipe

“The Web of Narcissus”: This 8,000-word review essay of Anton Barba-Kay’s A Web of Our Own Making develops further some of the themes in the “Stop Hacking the Human Person” essay and indeed Called to Freedom: digital technology arises from within a warped perspective on human nature and a quest for radical freedom, but it also creates a feedback loop where we increasingly twist ourselves to fit the medium. In the final section of the essay, I seek to move beyond Barba-Kay’s grim diagnosis to offer some proposals on how we might begin again to govern our technologies toward more human ends. Should publish 2/24.

“In Search of a Free Market” (Comment): In this essay, adapted from chapter 6 of my book, I look at the modern ideal of the free market as the maximization of consumer choices and explain just why this freedom leaves us feeling so empty—and what is necessary for a truly free market. Should publish 2/6.

Podcast Appearances: I’ve recently recorded podcast interviews with The Classical Mind, The Theology Pugcast, Aaron Renn, and Gospel Simplicity. All four podcasts were interviews about Called to Freedom, but each of them went in different directions highlighting different themes, and they were all fun conversations where I enjoyed fleshing out key ideas.

Get Involved

If you like this Substack, please spread the word with others. For now, this Substack will be totally free, but if you like the work I’m doing, please consider donating to it here by supporting EPPC and mentioning my name in the Comments.

If you have any questions or comments or pushback on anything you read here today (or recommendations for research leads I might want to chase down), please email me (w.b.littlejohn@gmail.com). I can’t promise I’ll have time to reply to every email, but even if you don’t hear back from me, I’m sure I’ll benefit from hearing your thoughts and disagreements.

Amazing work. This is something I've been trying to get at in a piece thinking through Neil Postman's medical technology chapter in Technopoly. Your concept of "hacking the human person" is exactly what has happened, dovetailing with his "ideology of the machine" in medicine, but also all of life.

Thank you for the essay. Well done.